No general would ever suggest you read this book, and maybe that is why you should make time to do it. The first person perspective offered by Kassabian is unpolished, irreverent, and told from a soldier’s perspective. In a world full of strategic challenges it is, in my view, a good thing for those making the decisions and grappling with the consequences to get an appreciation for what the greatest of plans looks like when 18-year-old Americans are sent forth to implement them.

#Reviewing Taliban Narratives

Students of the Afghan conflict, information operations officers, public affairs professionals, diplomats, relief workers, and those working in the intelligence and psychological operations arenas would all be well served to have this reference close at hand. One can only hope the failures Johnson cites are not repeated, and, if the war cannot be won by the West, perhaps this book can help the Afghans find an honorable and enduring conclusion.

#Reviewing Earning the Rockies

It was America’s good fortune—Manifest Destiny if you will—to rise on a temperate continent with abundant resources. Great Britain ceded its empire in part because it could trust and rely on the United States. America does not share this luxury. Pragmatism must be America’s watchword, for neither isolationism nor unilateralism will work.

In Search of Strategy. In Search of Ourselves.

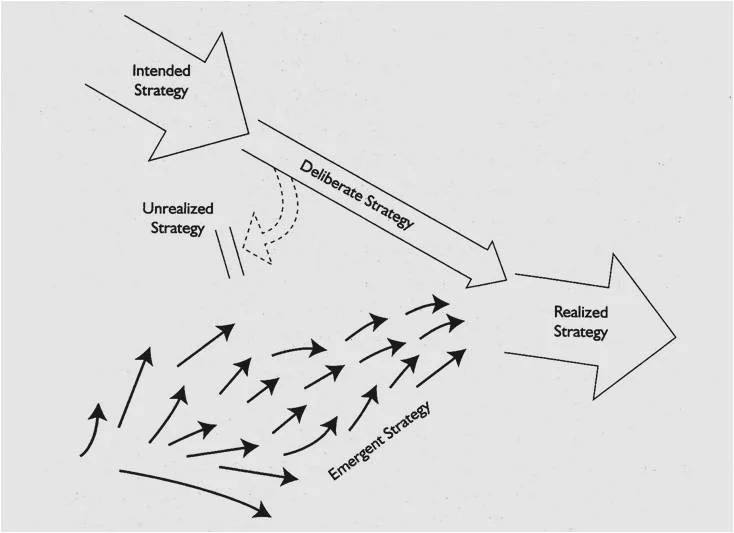

Good strategy explains why we do what we do. It ties together a nation’s political objectives with the resources at hand; it gives purpose to the tactical actor. Bad strategy muddles these things into a slurry that lacks sufficient consistency to be of use to anyone. The pieces can’t be seen for the whole. Adding more ingredients and blending more doesn’t make it better, neither does renaming it.

Green on Blue: An Interview with Elliot Ackerman

Green on Blue is the story of an Afghan child born to war, scarred by conflict, and driven by his enculturated need to respond to violence with violence. Aziz is his name. If you’ve served in Afghanistan and worked with the Afghan National Army, the National Police, or even if you’ve come across men who seem to live normal lives, you have probably met him; though it is unlikely that you understand what motivates him, what drives him to act, or what he fears.

Knowing and Not Knowing: The Intangible Nature of War

The Boy Soldier tells us all we need to know of war. He intrinsically knows, as all soldiers do, exactly what is about to happen. Yet the boy, and every other soldier from time immemorial, could not possibly know what shape their experience would take. How war would change them, and change under them. Horses replaced by machinery. Open trenches rendered useless by artillery. Static defenses circumvented by maneuver warfare. The world’s sole superpower maimed one man at a time by homemade bombs. This is war: universal and unique. This is Dunsinane.

The Cain and Abel Moment for Military Aviation: Inside History's OODA Loop

We do not know on what day or on what battlefield the first two men engaged in mortal combat. Nor do we know the first time that two ships came abreast of one another and lashed together their crews fought to the death. We do know the first time that man expanded the realm of combat into the skies.

Does knowing this change anything? How is capturing an initial moment different than only knowing of its effects and outcomes thousands of years later? Is knowing the shape of a thing at birth critical to understanding its applications later on? These were the questions I found myself asking after reading Gavin Mortimer’s The First Eagles last month.

To say that things were changing rapidly would be a terrible injustice.

Mortimer chronicles the story of a cohort of restless American innovators who apply a bit of disruptive thinking, denounce their citizenship and join the fledgling Royal Flying Corps. The newness of the offensive application of force in the physical space now known as the “air domain” is self-evident on every page. Reading this book was literally like watching a child learn to ride a bike without any instruction or guidance save that of his equally inexperienced friends. The recency of the innovation of flight and the pace of change is staggering. Just a few years after the first controlled flight at Kitty Hawk, pilots were dueling at over ten thousand feet. This leap forward is coupled with photographs of soldiers mounted on horses inspecting downed German fighter planes. To say that things were changing rapidly would be a terrible injustice.

Is it fair to look back from the passing of just a hundred years and critique ourselves for having not learned from these mistakes?

“Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it,” is a familiar maxim. It is also devoid of the context of time. What is history? How long does an event take to be considered historical? In The First Eagles readers are exposed to the initial experimentations with military aviation by those who would become leading practitioners a few years later. The mistakes made are multitude and familiar yet these events can be observed without judgment. After all, no aviator in the First World War was repeating a mistake previously made. They were operating in a domain that was ahistorical. Is it fair to look back from the passing of just a hundred years and critique ourselves for having not learned from these mistakes?

As I read through the book there were events with a familiar refrain to them, as if I had seen or heard of them before.

When the Germans dispersed their superior attack aircraft across different units instead of building a cohesive, lethal organization they committed what is now known to be a fundamental mistake. The allies were able to overcome the German technical overmatch through improved tactics, returning balance and then regaining superiority in the air. The US Army Air Corps would face similar challenges with the dispersion of strategic assets at the tactical level in the early days of the Second World War. One could argue that the US Air Force, still struggling to determine exactly what its role in future conflict will be, is facing a technical overmatch — tactics problem of epic proportions today.

When some of the first American aviators serving with the British were recalled to serve as instructors in the developing Aviation Section of the US Army Signal Corps, they were not welcomed for their experience and knowledge. Rather their status as innovators and disruptive thinkers — men who acted before their institutions were ready — caused them great pain. They were belittled, disrespected and treated with a callous indifference that smacked of both envy for what they had accomplished and an institutional rigidity that left little doubt about the pace of change. It seems that talent management is a long-standing problem in the American military.

Innovations are in their purest form when first crafted. They are bare, organic, utilitarian versions of what they will become. In an effort to break the stagnant environment of trench warfare the idea of a multi-role aircraft emerged. On August 8th, 1918, the opening day of the Allied “Hundred Days Offensive,” aircraft designed for aerial combat were retasked to conduct bombing missions and other close air support activities. The results were nearly catastrophic for allied aviation. The bridges and other infrastructure targeted were too sturdy for the twenty-five pound “Cooper bombs” carried by the light aircraft and the low altitudes required to engage the targets subjected thin-skinned planes to withering ground and anti-aircraft fire. Nearly twenty-five percent of all aircraft that flew low-level missions that day were lost or rendered unflyable. The next day, the allies reassigned fighter aircraft to escort duty and left the bridge busting to the bomber squadrons. This lesson was literally learned in a day and yet, nearly a hundred years later, we still struggle with the compelling need to do less with more and strive to fill every niche in the air domain with a multirole aircraft.

These are just three lessons that were eerily familiar to me as I read through The First Eagles. There have certainly been advancements in the air domain that were built on capabilities developed in these first, pre-historical days of modern aviation. Parachutes are introduced, training protocols developed, maintenance schedules refined and improved as well as the obvious emergence of aerial tactics and strategy. With that said, the book left me asking more question of my own service and our ability to change than it answered about our history.

Is a hundred years enough time to have learned from our mistakes? Is a hundred years enough time for us to observe our Cain and Abel moment, orient ourselves to the problem, decide and act; or is history operating inside our OODA Loop?

Tyrell Mayfield is a U.S. Air Force Political Affairs Strategist. He serves as an Editor for The Strategy Bridge, is a founding member of the Military Writers Guild, and is writing a book about Kabul. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Confessions of a Struggling #Professional: Summarizing the #Profession series

The reason I enjoy continuing this conversation on The Bridge is because many of our “professional” counterparts are interested in having it. I think I have a better idea about where I stand, and where our military stands with respect to this conversation and I urge all of you to pursue a professional standard and think about the ethical requirements that it entails.

The Intersection of #Profession and Ethics: Redefining the Modern Military

As good professors so often do, D. Shanks Kaurin's initial query of three simple questions spawned a series of follow-on questions. Does Samuel Huntington’s oft-cited definition of a military profession in The Soldier and the State still ring true in the 21st century? Does training and continuing education play a role in defining a profession? Is a universal code of ethics required?

Fighting the Narrative: The First Step in Defeating ISIL is to Deny it Statehood

Before the physical battle to defeat ISIL begins, the narrative surrounding that fight must be clearly delineated and thoughtfully parsed. The first step in defeating ISIL is to deny it statehood. The second step in defeating ISIL is to ensure that the states of Iraq and Syria have strong, legitimate, and sovereign governments — whether we like them or not.