Looking to the future, as the military grows to incorporate full benefits to same-sex couples on base and more inclusion of women in combat roles, could the next generation of Military-Americans actually become the country’s most accepting of diversity?

#Reviewing "The Strategist"

Sparrow’s account of Scowcroft is full of insight and surprises. Readers will take pleasure in Sparrow’s depiction of the NSC debates, executive-level relationships, and the nuanced recollections of a consummate strategist. Anyone interested in understanding the unique role of the NSC in foreign policy and executive-level decision-making during the Nixon, Ford, Reagan, or first Bush administrations will be interested Sparrow’s work. This book also has practical use for journalists, political scientists, as well as students of U.S. security strategy, foreign policy, and American government.

When does Putin become our Stalin?

Russia’s President, Vladimir Putin, governs over the largest landmass on earth, the world’s 2nd largest nuclear arsenal, and over 140 million people. Putin has been criticized as being cold, calculating, and autocratic. He has taken offensive measures in Crimea and Georgia, aggravating European leaders and resuscitating Cold War nostalgia and fear. Furthermore, Putin vehemently refuses to concede to rebel forces in Syria, despite President Bashar al Assad’s wartime atrocities and his illicit use of chemical weapons. While many argue these acts are evidence of Putin’s ruthlessness, they also reveal calculated and strategic foresight.

History's Last Left Hook?

One of history’s first large scale “left hooks” took place during the Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage. The fundamental principles of that ancient conflict can be seen in World Wars I and II, and even Desert Storm: all these “left hooks” share the common principles of surprise, shock, timing, overwhelming force, precision, and deception; they are military envelopments with strategic implications.

#Monday Musings: Diane Maye

Fiction for the Strategist

Now, it is dangerous to propose that the real world is just like a fiction world. Strategists should not just look to one genre or story to explain reality. But, there are many elements of the fictional world that are present in the real world. Fiction can serve as a metaphor for complex ideas and illustrate challenging ideas about human nature.

Out Jihad the Jihadi

In a lecture to field grade officers at the U.S. Army War College in 1981, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Maxwell Taylor described strategy as the sum of ends, ways and means; where ends are the objectives one strives for, ways are the course of action, and means are the instruments by which they are achieved.

We know how to strike, but can we achieve victory?

The U.S. military has been, without a doubt, innovative during the past century of warfare. Advances in technology have allowed the U.S. armed forces to become the most expeditionary, precise, and lethal force in the world. During the Cold War, the bulk of defense spending went towards countering the Soviet threat. In the end, the strategy was a success; the Soviet Union fell without direct confrontation. In the meantime, the U.S. military’s culture adapted to the political and economic realities of the Cold War. Although the Cold War has technically been over for 25 years, elements of that era’s defense culture have proven extremely resistant to change.

When It's Personal #Profession

I teach an undergraduate course on International Relations at an online university popular with military students. During one of my classes, two of the students, one a former Reconnaissance Marine and the other an Army Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) technician, had a lengthy discussion about their frustration with US foreign policy. Both of these students had spent a considerable amount of time in Iraq, both in forward combat positions. The EOD technician was especially upset with the rise of the “Islamic State” in Iraq over the past year. I routinely encourage my students to talk about their military experiences, which they do. Most of the time they share some interesting perspectives, but this student truly caught my attention when he discussed his perceptions of Iraq. He said, “the loss of life is exactly why I’m frustrated watching every city I spent time in crumble beneath the weight of ISIS. It is the most severe tragedy I have ever had to endure.”

…the loss of life is exactly why I’m frustrated watching every city I spent time in crumble beneath the weight of ISIS. It is the most severe tragedy I have ever had to endure.

In response, the Marine student replied, “I separated myself very quickly from our actions and their success…They were given the tools to make it happen and it is up to them. Ultimately I do not care if the cities and nations I fought in crumble to the ground, as it is not my responsibility to keep them safe. My responsibilities were tied to accomplishing the given mission and bringing back my Marines, that was it.”

My responsibilities were tied to accomplishing the given mission and bringing back my Marines, that was it.

While the EOD technician feels deeply frustrated about US foreign policy for personal reasons, namely the loss of life, the Marine has been able to distance himself from recent events. For him, the mission ended when he left Iraq, and he feels nothing personal about the situation taking place on the ground now.

The dialogue between these two young men resonated with me quite deeply. I think their conversation precisely reflects two distinct ways of assessing a wartime experience: one professionally and one personally. Much like them, I have often questioned my own interest in our foreign policy in Iraq: is it professional or is it personal? I spent time in Baghdad during the surge and witnessed hundreds of reconstruction, reconciliation, and good-will projects in the country. I have quite a few professional contacts that are either Iraqi or have worked in Iraq. My PhD course work focuses on Iraqi politics, and I have a serious academic interest in the history of the country. Yet, as an academic, I have a duty to remain objective and impartial in my analysis of the political situation.

Despite this professional stance, I do feel personally responsible for mistakes our government has made. When I saw how swiftly the Islamic State took Mosul and sections of Anbar province last year, I was not only horrified and disgusted, but I also felt disillusioned, and I felt like my very own mission in the country had failed. Not only that, I was profoundly disturbed with how we treated Iraqis that came to the aid of the U.S. military during the surge. For instance, without the Sons of Iraq, the momentum from the surge probably would not have turned the tide on Al Qaeda so quickly. Yet, we abandoned our moral obligation to help these young men, and instead used them for political collateral. After six years, it is very hard for me, as an American, to look these people in the eye. Perhaps its the lurid and visceral nature of war that distinguishes it from most professions, and those situations can feel so deeply personal.

So, did my personal responsibility for the situation end when I left Iraq? For me, it did not. Although, I do think that for most people this is a very good way of coping with their wartime experiences. If I happened to be in a different profession, then yes, perhaps I would have the same mentality as my Marine student. For instance, if I was an active duty serviceman, I would likely distance myself, mentally, from the events that took place in Iraq, especially the ones that were beyond my control. Personal feelings can cloud judgment and rational decision-making. It is difficult to remain objective, and having personal feelings can make it even more difficult to “move on” from a negative situation. When faced with negative situations in the workplace, it is best to keep it professional, and accept responsibility where responsibility is due. When the mission is over, put it to rest, because thinking about past events is highly unlikely to change them.

…I’ve still made a conscious decision to take personal responsibility for what I see as a great failure in American foreign policy and decision-making.

Yet, despite this, I’ve still made a conscious decision to take personal responsibility for what I see as a great failure in US foreign policy and decision-making. I believe this is the responsibility I bear as an American that was involved in the conflict. And, while it is a tragedy, I also see it as a chance to learn. I think most people going to be split on how to approach this subject, and I would be very curious as to what others think about it. My own thought is that the true professional must constantly balance their obligations to their employer or service against their personal experience, knowing that a certain amount of empathy and ownership is required in order to process wartime events in a way that is both humane and just.

Diane Maye is a former Air Force officer, defense industry professional, and academic. She is a PhD candidate in Political Science at George Mason University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author. This post was inspired by Tyrell Mayfield who, speaking on his own experiences in Afghanistan stated, “I’m personally vested, which is different than a professional obligation.”

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

The "Islamic State" and the #FutureOfWar

Why They Are a Junior Varsity Team

When asked about the “Islamic State” last year (then referred to as ISIS), President Obama stated that, “if a jayvee team puts on Lakers uniforms that doesn’t make them Kobe Bryant.” After the Islamic State swiftly overtook Mosul and much of western Iraq last summer, media pundits and politicianscriticized the analogy. This essay argues the opposite, President Obama was absolutely correct in referring to the Islamic State as a “JV” team, and how policy makers conceptualize the world order and its threats has enormous implications for the future of war.

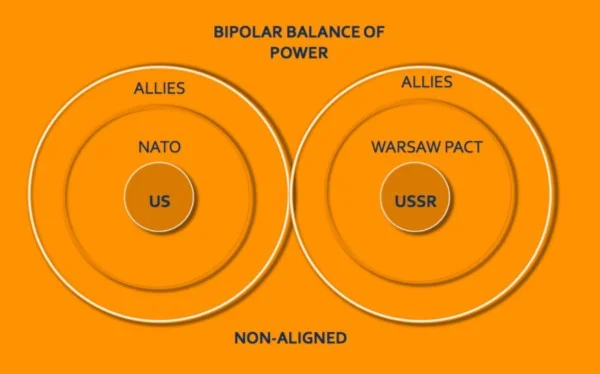

In order to conceptualize the future of war, one must understand the strategic setting (or world order). Nearly two decades ago, Barry Posen and Andrew Ross offered competing visions for U.S. national security by offering a typology for U.S. grand strategy, each with a preferred world order[1]. Instead, this essay suggests that grand strategy is not the driver of world order, but rather world order is the driver of grand strategy. Each strategic setting constructs a different type of world, with different centers of political, military, and economic power. The three scenarios in this thought experiment are: bipolarity (two antagonistic superpowers), unipolarity (one superpower) and multipolarity (multiple regional powers). These poles represent a “center of gravity” that strong nation-states generate with the weight of their economic, political and military systems.

…grand strategy is not the driver of world order, but…world order is the driver of grand strategy.

Scenario 1: Bipolar World

Neorealists such as Kenneth Waltz and Robert Art argue that the bipolar world order is the most stable. According to the neorealist literature, bipolarity tends to be the preferred world order from the U.S. security perspective because total war is unlikely between two nuclear-armed states, and only a nuclear-armed state can rise to superpower status. Instead, wars in bipolar worlds are typically proxy wars fought on the edges of hegemonic influence. The proxy wars of the Cold War, most notably the Soviet incursion in Afghanistan and the U.S. incursion into Indochina, are typical of wars fought in a bipolar world. One superpower intervenes abroad, outside their sphere of influence, and the other tries to undercut their actions. If China were to emerge as a peer competitor this century, the U.S.’s ‘Pivot to Asia’ is a logical security strategy, as most of the proxy wars with China are likely to take place in the Pacific theater of operations (but not in China itself).

Conceptualization of a Bipolar Strategic Setting

One characteristic of a bipolar world order is that it gives smaller players on the world stage an alternative to the U.S. for alignment and security assistance. For instance, during the Cold War, Egypt balanced U.S. influence by alternating between Moscow and Washington for political sponsorship, military training, monetary benefits and arms procurement. If China, or even Russia, rises to the level of a peer-competitor, “mercurial allies,” such as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) would be faced with a choice: either align with U.S. interests when seeking security assistance, or seek assistance from the other superpower.

Scenario 2: Unipolar World

The sun never set on the British Empire. (Wikispaces)

In the unipolar world, a single hegemon drives the world order, much like the Roman or British Empires did at their heights. Given the vast economic and military power of the U.S., some analysts suggest the global order for the next several decades will be unipolar. Certainly this was the general consensus after the collapse of the Soviet Union a quarter century ago. In this scenario, strategically speaking, the U.S. will have to resolve a major incongruity in the national political-military culture: distaste for imperial behavior, yet the desire to expand commercial enterprises and protect human rights abroad. Likewise, U.S. strategists will have to face an inherent paradox: every nation-state resents the hegemonic superpower, but every nation-state is seeking to become the hegemonic superpower.

The U.S. will have to resolve a major incongruity in the national political-military culture: distaste for imperial behavior, yet the desire to expand commercial enterprises and protect human rights abroad.

In this scenario, as the unipolar power, the U.S. will be called upon to intervene in regional conflicts. Without a clear national security strategy, U.S. policy makers will pick and choose battles in an ad hoc manner, administration by administration, driven by short-term political agendas. Yet, U.S. actions abroad will have unseen second and third order effects that will endure for decades and even centuries to come.

The realist would argue that as the unipolar power, the U.S. will naturally desire to retain supremacy and contain any potential peer competitors. Therefore, expansion of NATO and security of the Pacific would drive national strategy (consciously or not): NATO to contain a revisionist Russia and military presence in the Pacific to thwart Chinese aggression.

In this scenario, the U.S. can also intervene in smaller regional conflicts at will. But, what kinds of conflicts does the superpower face in a unipolar world? These are the same types of battles faced by the Roman and British Empires, and much like bipolar scenario, they will take place at the edge of the hegemonic influence. So, you can expect the U.S. to become involved in smaller regional conflicts around Russia’s borders, between Turkey and the Middle East, and around the Mediterranean and Pacific Rim.

Scenario 3: Multipolar World

In a multipolar world, there is no single superpower. Interdependence and transnational interests cloud the traditional notion of the “nation-state.” And, without strong nation-states to hold players accountable, there is a very high threat of everything from nuclear proliferation to cyber attacks from rogue organizations. Furthermore, cooperative security arrangements through multinational institutions mean priorities shift and change all over the world, all of the time.

...without strong nation-states to hold players accountable, there is a very high threat of everything from nuclear proliferation to cyber attacks…

A political realist could argue the emergence of the Islamic State today is a direct reflection of the fallout from a lopsided world order. Without Russia and the U.S. aggressively supporting the nation-state system and propping up regional powers, ungoverned spaces are left in a turbulent security vacuum. And, in an ominous foreshadowing of future events, Posen and Ross suggested “the organization of a global information system helps to connect these events by providing strategic intelligence to good guys and bad guys alike; it connects them politically by providing images of one horror after another in the living rooms of the citizens of economically advanced democracies”[ii].

According to Posen and Ross, a multipolar world begets multilateral operations. The U.S.’s contribution to military operations are typically where they have the most significant comparative advantage: aerospace power. Therefore, the future of war in a multipolar world sees the U.S. leading air campaigns against shifting enemies, mainly in failed states. Not only that, the U.S. will aggressively seek to maintain their comparative advantage in aerospace power.

Realists argue the multipolar world is the most chaotic. First, without a strong superpower to support smaller nation-states, smaller players cannot maintain a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. Weak and failed states tend to spew a plethora of competing factions, some with nefarious intentions. Second, the aggressors are unclear. Some factions are supported by regional hegemons, and others are simply trying to fill the power vacuum. Finally, the U.S.’s reliance on aerospace power makes U.S. forces even more vulnerable to asymmetric attacks. The non-state actor is unlikely to strike using conventional methods, so the battlefield is cast with ambiguous players, many of which are supported by regional hegemons.

Conclusion

*Quasi-nuclear denotes states with nuclear aspirations or undeclared nuclear capability

It is difficult to discern which world order is preeminent now, but it is possible the three world orders are not mutually exclusive, nor are they static conditions. Without a doubt, the U.S. has the world’s strongest economic and military systems, which suggests they are the lone superpower. Despite this, the world is actually experiencing many of the consequences derived from a multipolar world order. This is especially prominent in the Middle East, where regional hegemons are not officially nuclear states (although several of them have the capability and will to go nuclear). So, perhaps the best way to conceptualize the world order is unipolarity in locations closest to the U.S. and elements of multipolarity in distant locations with regional hegemons. Despite their differences, unipolarity and multipolarity both suggest that the future of war will be fought on the fringes of U.S. influence, against smaller and more agile adversaries- some of which have the ability to strike the U.S. homeland, many that are getting support from a regional hegemon, and most of which are the excrescence of a failed state. This is exactly why the Islamic State is a “JV” team. At this time, the Islamic State neither has the resources nor the capability to achieve the hegemony that comes with nuclear power and projection; they are simply a satellite of a larger hegemon. The U.S.’s response to the Islamic State typifies the future of war in a multipolar world: broad coalitions and the use of aerospace power against disparate organizations.

…the future of war will be fought on the fringes of U.S. influence, against smaller and more agile adversaries…

The main issue for U.S. policy makers is not from the chaos surrounding terrorist organizations like the Islamic State. Too much time and attention has been placed on this foe while ignoring much more important issues. For instance, global conditions are going to force the Department of Defense to place the primacy on maintaining air superiority, yet many conflicts of the near future will require the techniques of agile, flexible, and rapidly-adaptable fighters. It is very important to have a force structure designed for the threats it will face. Another issue will be how the global balance of power shifts if Iran, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, or Israel becomes a declared nuclear state. If just one of these states goes nuclear (officially), it is highly likely to set off an arms race in the Middle East. More importantly, recent incursions into Crimea and Ukraine demonstrate that President Putin is intent on implementing his revisionist agenda. Given that Russia is a nuclear power and the proximity of Ukraine to NATO allies, this is the biggest threat to U.S. security interests. But, even more dramatic and uncertain will be if a non-state actor is to acquire a nuclear weapon. U.S. policy makers will no longer be dealing with a JV team if the Islamic State (or any other terrorist organization) was to obtain a “loose nuke.” To use a sports analogy, it will be the equivalent of a JV high school basketball team having LeBron James in the starting lineup: they are probably going to win a few games against older and more experienced teams.

Diane Maye is a former Air Force officer, defense industry professional, and academic. She is a PhD candidate in Political Science at George Mason University where she studies Iraqi politics. She is a proud associate member of the Military Writers Guild. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Posen, Barry and Andrew Ross. “Competing Visions for U.S. Grand Strategy” International Security 21:3 (Winter 1996/7): 6.

[2] Ibid, 25.

Correct Answers and #Profession

Last week the Army War College released a study about military officers lying on a regular basis [1]. These lies include everything from misreporting training status to inflating performance reports. But, how much of this is blatant lying versus simply providing the “correct” answer?

Providing the “correct answer” is something that begins the first day of basic training, and it becomes an institutional norm. For instance, how many times has an entire squad of basic trainees replied, “YES DRILL SERGEANT,” to a question posed by their drill sergeant? This is the “correct” answer. The correct answer isn’t “No,” or “Yeah,” or “I don’t remember.”

U.S. Air Force Academy Form “O-Dash-96"

In my own experience, I found that basic training reinforces particular behavior and norms. For instance, new (basic) cadets at the Air Force Academy are given a survey after their first or second meal at the school. Officially, its an Air Force Form O-96, and contains six simple questions about the meal. The cadre instructs the basic cadets to fill out this survey. How was the food service? How was the attitude of the waiters? How was the waiter service? How were the beverages? What size were the portions? And finally, how was the meal? Not knowing the cadet system, as a young basic cadet, I answered the questions truthfully and honestly. How was the service? I thought it was slow! What was the portion size? I thought it was oversized. How was the meal? I thought it was unsatisfactory. I found out very quickly that these were not the “correct” answers. The correct answers (in order of the questions) were: fast, neat, average, friendly, good, good. Every cadet learned that these were the answers to the six questions on the form. It had to be filled out in this way. No other way was acceptable. This simple list of six answers is an institutional norm, a meme, which transcends every Air Force Academy class. But, this sort of correct behavior goes beyond basic training and tradition-building exercises, it can be found in most facets of military life. The “correct answer” is not so much the answer to the question, as it is a way of teaching conformity, uniformity, and mental discipline. Despite being deceptive, these are all characteristics of a well-trained military.

…the lessons of basic training don’t clearly elucidate the dichotomy between the truthful answer, and the “correct” answer, which may instill a culture that finds it acceptable to provide the “correct” answer all of the time.

Now, the lessons of basic training don’t clearly elucidate the dichotomy between the truthful answer, and the “correct” answer, which may instill a culture that finds it acceptable to provide the “correct” answer all of the time. But, this issue isn’t confined to the military alone. Large, complex, institutions are beset with internal systems, procedures, and layers of bureaucracy. Because of this, often the “correct” answer trumps the “truth.” How many times in my life have I given the “correct” answers versus the truth? It goes beyond procedure and formalities; we actually see this inconsistency all the time in our daily lives. For instance, I was on the phone with my bank recently and they wanted to know the color of my car (my security question). Well, I thought, I have two cars — one is black and one is blue. But, after much discussion, I found out that this is not the “correct” answer. The correct answer is silver, which was the color of the car I had when I created that account. But, this answer is not the truth, hence, the contradiction. But, the very point of the question is not to find out the color of my car, just like the point of the survey was not to find out about Basic Cadet Maye’s opinion of the meal. The point of the security question was to validate my identity. The point of the survey was to indoctrinate and train.

Oftentimes the “correct” answer saves you time and energy, and oftentimes it’s a matter of priorities. Providing the “correct” answer helps you focus on the mission you deem to be the most important for your people. That is not to say that the “correct” answer is always the best answer. But, it in a culture that routinely trains people to provide the correct answer, it can be difficult to distinguish the difference between the two.

Diane Maye is a former Air Force officer, defense industry professional, and academic. She is a PhD candidate in Political Science at George Mason University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the US Government or the Department of Defense.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] “Lying to Ourselves: Dishonesty in the Army Profession,” by Leonard Wong and Stephen Gerras, 2015, Strategic Studies Institute, Available from:http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=1250