The heart of leadership, especially within the profession of arms, is summarized with a single word: influence. Influence is the ability to have an effect on the character, development, or behavior of someone or something. As leaders, we must begin by first and foremost understanding this fundamental principle. People can be influenced one of two ways: through mandate leadership or through organic leadership. Understanding these two very different approaches to influence will in large measure determine not only what type of leader we are, but also the effectiveness of our leadership in shaping the behavior of others.

Coaching 2.0: Developing Winning Leaders for a Complex World

Coach, Counsel, Mentor. Every leader uses these developmental methods...or do they? These principal methods are the cornerstone of leadership development used by all the military services. However, we are only trained to implement two of them. This is a problem because, in the military, we grow our own leaders.

Brand U: Five Reasons Why Your Personal Leader Brand Matters

Brand matters. Whether you’re talking about Apple computers, Breitling watches, or Coca-Cola products, how a brand is perceived is important. It creates value. And the higher the perceived value, the more revenue the brand generates. So why should it be any different for you? Shouldn’t your personal leader brand be synonymous with quality performance? Don’t you want your name to be first on a senior leader’s mind for career opportunities and assignments? Don’t you want to be perceived as someone who adds value to any leadership team? Yet most of us overlook our leader brand. We take it for granted. If – and that’s a strong if – we even consider our brand. Because, to be completely honest, most of us don’t.

The Three Streams of Leadership

In short: three different streams of leadership — structural, relational, and imaginative — each produce distinctive cultural flavors, and a healthy unit exhibits a mix of all of them. A good leader will use their strengths in one stream to cover down on their weaknesses in the others, in the company of comrades, and in service to the mission and their people. A toxic leader corrupts these streams in pursuit of their own agenda, and each of the three has distinctive flavors of corruption. Therefore, we have three streams and two valences — selfless and selfish.

Cognitive Training to Achieve Overmatch in the #FutureOfWar

The future of war is hard to predict and we have rarely foreseen the next conflict before it has found us. As we transition out of large-scale counterinsurgency and security force assistance operations towards decisive action operations in our training focus, we must pay special attention to what and how we train in this environment. Some might wishfully think that the Army can return to a Cold War-like era where we have a laser focus on the fundamentals of shoot, move, and communicate within the construct of combined arms maneuver. However, the Army’s experiences over the last ten years, and current projections about the future implore us to seek other models to guide our preparation. The Army’s Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) recently published TRADOC Pam 525–3–1, The U.S. Army Operating Concept: Win in a Complex World to help define the future operating environment and challenges.

The Army Operating Concept lays out five characteristics and twenty warfighting challenges that can help guide the Army in its preparations for the future of war.[1] The five characteristics are the increased velocity and momentum of human interactions and events; potential for overmatch; proliferation of weapons of mass destruction; spread of advanced cyberspace and counter-space capabilities; and demographics and operations among populations, in cities, and in complex terrain. A common trend across these characteristics is the complex, massive volume of stimuli soldiers will face, and the decentralized decision making required to gain and maintain the initiative in the future.

In the future, the fog of war will be as much about too much information as it has been defined by the absence of information in the past.

Consider the following: urban terrain presents a plethora of stimuli and distractions to the future warfighter. Information collection assets and digital systems present the decision maker with an abundance of data that needs to be analyzed and synthesized into a shared understanding and future operations. All the while, a thinking and decentralized enemy will demand that the Army presents them with multiple dilemmas using innovative ideas, or else we risk ceding the initiative to our adversaries. An interesting aspect of the scenario above is that there is no mention of the basics as we traditionally view them, “shoot, move, and communicate.” Building adaptive and innovative leaders is the best way to win the next war and this can be accomplished by training the cognitive abilities of our soldiers and leaders.

What are the Critical Cognitive Abilities?

The Army Operating Concept mentions the requirement for advanced cognitive abilities within the context of the Human Domain and decision making, but it does not provide any specifics on what or how the Army should pursue these. Army doctrine does not currently address these issues either, so we should look to the fields of cognitive science and systems theory for specifics. The combined theories of these two fields provide us with a decision making model to help identify advanced cognitive abilities. Cognition begins with gathering information and proceeds to processing information, analyzing and synthesizing a conclusion and/or course of action, and finally executing the selected course of action. This model will form the basis for re-examining the scenarios presented previously.

The plethora of stimuli in urban terrain, and the abundance of data that can be gathered from modern information collection assets, challenge soldiers on the battlefield — all of whom must make life and death decisions. In fact, scientific studies support the fact that information overload often results in a decreased quality of decisions.[2] To help overcome this challenge, we must seek to increase our soldiers’ ability to gather information through the filter of trained perceptiveness. Soldiers who are trained in perceptiveness can use these skills to sift through excessive stimulation and recognize significant cues. This advanced situational awareness can help us identify anomalies and indicators to find the proverbial needle in the haystack.

Perceptiveness will provide us with a heuristic technique to assist us in our decision making.[3]

Once soldiers have collected the relevant information, they must then process and synthesize the information into concepts that can be executed as a course of action. Speed of mental processing and the ability to synthesize data into relevant concepts are desirable skills for anyone, but for a soldier this might mean the difference between life and death. So we must ensure our soldiers have these abilities. These skills are particularly advantageous in an age where the global media scrutinizes the decisions of leaders at every level.[iv] Speed of mental processing and synthesis are abilities traditionally associated with staff officers and NCOs, but all soldiers must seek to increase these abilities to gain and maintain the initiative in the future.

Finally, the future will inevitably present soldiers with an adaptive enemy, unique situations, and complex operating environments. These characteristics will require soldiers to apply trained tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) in foreseen circumstances, while having the ability to modify or invent new TTPs in real time for unforeseen situations. The key to adapting and overcoming these challenges in the future will be to foster a spirit of innovation in our soldiers.

How are we training these Cognitive Abilities Now?

Currently, the Army does not deliberately focus on advanced cognitive abilities in its leader development or collective training efforts, but in the future it must do so to achieve overmatch against our adversaries.

The discussion above highlighted four critical cognitive abilities that the Army must focus on: perceptiveness, speed of mental processing, synthesis, and innovativeness.

The Army has a handful of programs that seek to improve perceptiveness and adaptability, but they are not well known and it is challenging for commanders to get their soldiers into these programs. The biggest challenge the Army will face in seeking to develop these attributes will be to design and integrate training and educational efforts to scale across the entire force.

In the near term, the Army has a few niche programs that commanders can pursue to train and educate our soldiers on these advanced cognitive abilities. A non-exhaustive list of existing programs include Advanced Situational Awareness Training, the Asymmetric Warfare Adaptive Leader Program, Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness or resiliency training, the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies (UFMCS) or “Red Team” training, and Leader Reaction Courses. Each of these programs directly or indirectly addresses at least one of the four critical cognitive abilities.

Photo Credit: Aniesa Holmes. A role player dressed as an Afghan border security officer helps a student enrolled in the Advanced Situational Awareness Training program observe a village from a distance, Oct. 4, 2013, on Lee Field at Fort Benning, Ga.

The Army’s Advanced Situational Awareness Training program of instruction seeks to increase our soldiers’ ability to identify patterns and therefore anomalies in our environment. This advanced awareness will help soldiers identify pre-event indicators that are significant to mission accomplishment.[v] Contractors originally designed Advanced Situational Awareness Training, but the Army has since incorporated it into various professional military education courses, including the Armor and Infantry Basic Officer Leader Courses.[vi] Many aspects of Advanced Situational Awareness Training continue to focus on overcoming the threat of Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs), but its program of instruction should be able to be expanded to train perceptiveness more broadly.

The Asymmetric Warfare Group’s Asymmetric Warfare Adaptive Leader Program course promotes critical, creative problem solving to reach innovative solutions to ambiguous situations.[7] This course is an evolution of the Outcomes-Based Training and Education methods that the Army Reconnaissance Course adopted in the mid- to late-2000s. The Asymmetric Warfare Adaptive Leader Program is focused on promoting adaptive leaders and decision making under the principles of mission command. This course guides students through a series of principles and exercises that educate and train soldiers on perceptiveness, synthesis, and innovativeness.

The Army’s Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Program, known primarily for its resiliency training, is designed to help improve human performance across the Army. The Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Program originated out of a desire to promote resiliency and mitigate against potential risks in our soldiers and military families, but the Army has expanded its goals to include all aspects of human performance. The Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Program has established a unique and valuable relationship between soldiers and psychologists. The Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness’ cadre of psychologists have a unique insight into cognitive abilities and the broader science that can be harnessed to promote mental processing and other cognitive functions in our formations.

The University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies (UFMCS), better known throughout the Army as the “Red Team,” is another resource that promotes cognitive abilities. Leaders frequently think Red Team training is primarily for educating and training military intelligence leaders to think like the enemy — an almost natural assumption based on their common name — but the UFMCS offers much more. Anyone who has attended UFMCS training, or a discussion facilitated through their instructional methods, can attest to the power of the tools they use to train divergent and convergent thinking. These thinking tools and instructional methods include mind-mapping, storytelling, asking whys, dot voting, meta-questioning, and circles of voices. These discussion and cognitive tools are valuable for analyzing and synthesizing information to reach conclusions or courses of actions.

Photo Credit: LTC Sonise Lumbaca. Soldiers from the 197th Infantry Brigade participate in an adaptability practical exercise using an obstacle course during the Asymmetric Warfare Group’s Asymmetric Warfare Adaptive Leader Program hosted at Fort Benning, Ga. November 2012.

Finally, many Army installations have Leader Reaction Courses that challenge groups of Soldiers to collectively solve unique problems. These courses are frequently used during initial entry training and are thought of as team building exercises, but they should not be limited to these instances. A Leader Reaction Course trains problem solving techniques by encouraging creative and innovative thinking. Each obstacle forces participants to think out of the box and generate unique solutions. Encouraging our soldiers to think like this will help develop innovative minds for the battlefield.

How can we Train Cognitive Abilities in the Future?

The Army must develop a holistic and integrated approach to developing advanced cognitive abilities within our soldiers, leaders, and units. Currently, the Army has a number of niche programs and courses that provide near term cognitive development as described in the previous section. However, to adequately prepare for the future of war, the Army must develop a more holistic short and long term plan to address these abilities. The Army must develop a system to assess and provide continuous training and educational opportunities throughout a soldier’s career.

To assist commanders in monitoring and tailoring their cognitive training efforts, the Army must develop a method of assessing cognitive abilities in all soldiers and leaders. Cognitive abilities can be assessed and recorded similar to how the Army currently tests enlisted soldiers to determine their General Technical (GT) score.[8] The Army must tailor these assessments to measure the aforementioned critical cognitive abilities. The Army’s Centers of Excellence could further shape these assessments to measure any additional cognitive abilities deemed relevant for soldiers in their respective Branch/MOSs. In addition to a mandatory assessment during a soldier’s accession into the Army, these assessments must recur throughout a soldiers career. This will enable individual soldiers to seek feedback and improve their cognitive abilities, while allowing commanders to assess their unit’s capabilities. The feedback provided by these assessments will help commanders develop comprehensive cognitive training plans that are nested with and enhance their leader development plans.

To improve cognitive abilities throughout the Army, the Army must expand current efforts into comprehensive short and long term training strategies. Two viable short term courses of action are to expand the current training capacity of these programs and/or rapidly spread these initiatives at the unit level through a train-the-trainer methodology. In addition to the initial benefits to the soldier, the train-the-trainer methodology is advantageous because it will provide a subject matter expert within each unit, similar to a master gunner or master fitness trainer. The master cognitive trainer can provide advice to the commander to incorporate cognitive training into existing training exercises and/or design stand-alone educational or training events as desired. These short term courses of action will generate additional resources for cognitive development until long range plans can be developed and employed.

In the long term, cognitive training and education should be developed based on the results of the aforementioned assessment tools and integrated into programs such as Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness. Integration with the Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Program will enable harnessing the unique capabilities of psychologists and advanced cognitive sciences. Additionally, optional courses should be offered at installation education centers and on-line to allow soldiers to develop cognitive skills as another aspect of self-development. The integration of assessment tools, expanded classroom and on-line educational opportunities, inclusion of cognitive development within Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness, and cognitive training incorporated into unit training and leader development programs have tremendous potential towards achieving overmatch against future adversaries.

Conclusions

The Future of War is hard to predict. However, it is increasingly obvious that the basics of shoot, move, and communicate must be expanded to include cognitive abilities. Perception, speed of mental processing, synthesis, and innovation are the four most critical cognitive abilities. We must develop a system to assess, train, and educate soldiers in these abilities to develop our collective capabilities. As mentioned in the Army Operating Concept, the Army must address advanced cognitive abilities and the Human Dimension to provide overmatch against our potential adversaries. Advanced cognitive abilities must be developed to gain and maintain the initiative in future conflicts.

The author would like to thank Mr. Keith Beurskens and the eleven captains in his small group at Solarium 2015. The thoughts above are reflective of this group’s efforts during a week-long discussion and research endeavor where they studied the Army Operating Concept at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Gary M. Klein is a U.S. Army Officer and member of the Military Writer’s Guild. The views and opinions expressed here are his alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Department of the Army, TRADOC Pam 535–3–1, The U.S. Army Operating Concept: Win in a Complex World, (Fort Eustis, VA: U.S. Government Printing Office, October 2014), p.11–12 and Appendix B. Pages 11–12 address the likely characteristics of future operating environments while Appendix B lays out the twenty warfighting challenges (aka questions) that will drive development of the future force.

[2] Crystall C. Hall, Lynn Ariss, and Alexander Todorov. “The illusion of knowledge: When more information reduces accuracy and increases confidence,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 103 (2007): 277–290.

[3] Heuristic techniques are mental shortcuts that help us make decisions in complex situations that would otherwise require a disadvantageous amount of time to use logic. Heuristics enable us with intuitive thinking as opposed to reflective thinking that encourage us to gather all information before coming to a conclusion.

[4] Joe Byerly, “#Human Element of Leadership,” on The Bridge,https://medium.com/the-bridge/human-element-of-leadership-fc85ff9df13, November 15, 2014, retrieved March 2, 2015.

[5] Harry Evans was the original designer for the Army’s Advanced Situational Awareness Training, see http://www.tacticalintel.com/counter-terrorism.html, retrieved March 2, 2015.

[6] Aniesa Holmes, “ASAT training helps develop critical thinking skills,” in U.S. Army News,http://www.army.mil/article/112916/ASAT_training_helps_develop_critical_thinking_skills/, October 9, 2013, retrieved March 2, 2015.

[7] Susan G. Straus, et. al., Innovative Leader Development: Evaluation of the U.S. Army Asymmetric Warfare Adaptive Leader Program, (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Research Paper, 2014).

[8] The GT score currently assesses soldier’s word knowledge, paragraph comprehension, and arithmetic reasoning:http://www.goarmy.com/learn/understanding-the-asvab.html, retrieved March 2, 2015.

Humble Leaders are the #FutureOfWar

The recent Future of War conference hosted by the New America foundation highlighted the anticipated complexities of future warfare, everything from autonomous platforms to biotechnology. In fact, the sheer volume of predictions was overwhelming, lending new truth to Sir Michael Howard’s oldobservation that the task of military science is “to prevent the doctrines from being too badly wrong.”

Complexity in warfare is not a new characteristic, but the expansion of warfare into new realms suggests an ever-growing list of challenges for military leaders. The growing spectrum of needed competencies exceeds the grasp of even the most talented leaders in our ranks. A new way is needed.

The Future of War is profoundly uncertain; therefore, adding humility to our conception of successful leaders is essential.

A recent Catalyst study suggests one option, which they label inclusive leadership. While this may feel like yet another round of buzzword bingo, a closer look at the components of inclusive leadership reveals characteristics that should be familiar to good leaders in the ranks. Specifically, inclusive leadership calls for leaders to use the skills of their peers and subordinates to bring the maximum amount of talent to bear on the problem. Three of the four characteristics of inclusive leadership have direct analogues in existing military leadership practice: empowerment, courage, and accountability.

But the fourth, humility, seems to fall outside of our accepted leader characteristics. In fact, the word itself has no mention in Army, Air Force, orMarine leader doctrines, and is only cited in passing in the Navy Leader Development Strategy. And while it may be that this is yet another example of Americans not following their own doctrine, many leaders would be hard pressed to remember the last time they heard of humility being celebrated as a military virtue. But humility is an essential response to uncertainty, because it allows leaders to remain open to new ideas and innovative approaches.

Critics of this idea might say that this is old wine in new bottles, as all of the service leader doctrines already contain some variation on the idea of selfless service. But selfless service and humility, although both essential, are profoundly different characteristics and actions. In fact, selfless service can work against an acceptance of uncertainty by encouraging leaders to put trust in ideas that they don’t understand and may even have deep reservations about. Humility, on the other hand, accepts that there may be concepts outside the leader’s grasp while still pushing to find someone who does understand those ideas.

The strongest argument against humility as an essential part of military leader practice is its equation to weakness. But just as all virtues become vices when taken to extremes, so can humility be moderated in a way that makes it effective. For proof of this, we can look to a historical vignette.

At 0400 on June 5th, 1944, GEN Eisenhower gathered his OVERLORD commanders for a decision on whether to launch the Normandy invasion on June 6th. After hearing a possibility of a break in the terrible weather that had postponed the attack by 24 hours, Eisenhower polled his commanders for their views. Finally, as Carlo D’Este describes in Eisenhower in Peace and War:

After everyone had spoken, Eisenhower sat quietly. [Chief of Staff Walter Bedell] Smith remembered the silence lasted for five full minutes…When Ike looked up, he was somber but not troubled. “OK, we’ll go.” With those words, Eisenhower launched the D-Day invasion of Europe, an enterprise without precedent in the history of warfare.

Note what was missing in the vignette above: no bombastic speeches, no cross-examinations, no demands for guarantees. In accepting that he had the best information he was going to have and moving forward on that basis, Eisenhower epitomized the humble leader and gave us a model of how humility can be incorporated with our other martial values to deal with the profound uncertainty of the future.

The author would like to thank the members of the Military Writers Guild for their insights on service leadership doctrine. Any errors remain those of the author alone.

This post is provided by Ray Kimball, an Army strategist and member of The Military Writers Guild. The opinions expressed are his alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Back to the Future

The Danger of Overconfidence in the #FutureofWar

From Operation Desert Storm to Operation Enduring Freedom, the United States Navy has enjoyed an asymmetric technological advantage over its adversaries.[1] Uncontested command and control dominance allowed American commanders to synchronize efforts across broad theaters and deliver catastrophic effects upon the nation’s enemies. These years of uncontested command and control dominance birthed a generation of commanders who now expect accurate, timely, and actionable information. High levels of situational awareness have become the rule, not the exception. The Navy and its strike groups now stand in danger of becoming victims of their own technological success. An overreliance on highly networked command and control structures has left carrier strike groups unprepared to operate effectively against future near-peer adversaries.

An overreliance on highly networked command and control structures has left carrier strike groups unprepared to operate effectively against future near-peer adversaries.

Data-Links Are Our Achilles’ Heel

Conceptual image shows the inter-relationships between sea, land and air forces in a Network Centric Warfare environment. (via RAAF/BAE Systems Australia)

The concept of Network Centric Warfare (NCW) was birthed from the realization that integrating many of these systems would “create higher [situational] awareness,” for commanders.[2] Forecasting the looming dependence on NCW, the now defunct Office of Force Transformation claimed, “…Forces that are networked together outfight forces that are not.”[3] Merging vast amounts of information together into one common operating picture is the most challenging element in NCW, and tactical data-links serve as the means for accomplishing this task.

The future of strike group warfare is a concept named Naval Integrated Fire Control (NIFC). Recently NIFC was rebranded NIFC-CA, accounting for additional counter air capabilities. NIFC-CA doubles down on data-links, particularly Link-16. A January 2014 United States Naval Institute News article boasted, “Every unit within the carrier strike group — in the air, on the surface, or under water — would be networked through a series of existing and planned data-links so the carrier strike group commander has as clear a picture as possible of the battle-space.”[4] Read Admiral Manazir, Director of Air Warfare added, “We’ll be able to show a common picture to everybody. And now the decision-maker can be in more places than before.” In spite of his enthusiasm for NIFC-CA, Rear Admiral Manazir reveals a serious problem. “We need to have that link capability that the enemy can’t find and then it can’t jam. The links are our Achilles’ heel, and they always have been. And so protection of links is one of our key attributes” (emphasis added). What Rear Admiral Manazir calls a “key attribute,” most professional military education students would instead call a critical vulnerability.

It is unfair to criticize any commander for wanting more of this informational power. But what happens when this information is threatened, degraded, or denied?

Strike group commanders now rely heavily on information shared across data-links, specifically Link-16, to build their situational awareness. This information sharing enables impressive capabilities: rapid decision-making, massing of force, and very quick after-action assessments. It is unfair to criticize any commander for wanting more of this informational power. But what happens when this information is threatened, degraded, or denied? This question is important, because despite ongoing efforts to harden tactical data-links against attack, eliminating the threat is impossible.

Unjustified Overconfidence

Today we know potential adversaries are developing cyber-space and electronic warfare capabilities to neutralize, disrupt and degrade our communications systems. The challenge is in balancing the benefits and advantages derived from using high-tech communications with the vulnerabilities inherent in becoming overly dependent upon them. — Christine Fox, Former Acting Deputy Secretary of Defense.[5]

The message Ms. Fox delivered is clear: we must not allow a fascination with technology to stand in the way of executing basic war-fighting functions. She went on to state that Cold War-era U.S. naval forces planned to lose communication capabilities against the Soviets, then asked what has changed? Why would the Navy not share that concern about other potential adversaries?

At 22:26 GMT, 11 January 2007, China slammed a kill vehicle into one of its dead metrological satellites, proving to the world that they were part of the small but unfortunately growing club of countries that can accomplish the difficult task of hypervelocity interceptions in space. As a signal to the world, this test highlighted both China’s technological prowess and the fact that China will not quietly stand by while the United States tries to expand its influence in the region with new measures such as the US-India nuclear deal. We have analyzed the orbits of the debris from this interception and from that put limits on the properties of the interceptor. We find that not only can China threaten low Earth orbit satellites, but, by mounting the same interceptor on one of its rockets capable of lofting a satellite into geostationary orbit, all of the US communications satellites. (via MIT Science, Technology, and Global Security Working Group)

In 2007 China successfully destroyed a satellite in orbit. In January 2014, the commander of U.S. Air Force Space Command, General William Shelton, stated, “direct attack weapons, like the Chinese anti-satellite system, can destroy our space systems.”[6] He added that the most critical targets are those satellites providing “survivable communications and missile warning.” Clearly, U.S. forces can no longer remain complacent. An enemy attack on Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites would severely affect a strike group’s ability to accomplish the most basic tasks to the most complex.

The portion of the spectrum used for Link-16 communications is the ultra high frequency (UHF) band. UHF communications are line of sight. (via “Understanding Voice and Data Link Networking,” December 2013, Northrup Grumman Public Release 13–2457)

Satellite denial is not the only area for concern. Several nations are now producing aircraft, ground, and naval vessels with advanced electronic attack suites capable of contesting coveted regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. In a complex network of data and sensor sharing, each node is a contributor, and some nodes are more critical than others. In some cases, enemy electronic attack need only attack the right nodes to have debilitating effects across the entire network. China is pursuing broadband jamming and partial band interference of the Link-16 network with that objective in mind.[7] According to Richard Fisher, an expert on China’s military with the International Assessment and Strategy Center, “…taking away Link-16 makes our defensive challenge far more difficult and makes it far more expensive in terms of casualties in any future conflict with China.”[8]

Fortunately, past exercises and experiences serve as a guide for the future.

As Deputy Secretary Fox and General Shelton have pointed out, the threat is real. If we accept that strike group commanders have become overly reliant upon networked command and control structures, and that these networks are vulnerable to attack, then commanders must have a clearer understanding of what operational impacts can be expected. Fortunately, past exercises and experiences serve as a guide for the future.

Back to the Future

“It is widely recognized that a carrier task force cannot provide for its air defense under conditions likely to exist in combat in the Mediterranean.” — Admiral John H. Cassady, Commander-in-Chief U.S. Naval Forces, East Atlantic and Mediterranean, 1956 [9]

Signalman Seaman Adrian Delaney practices his semaphore aboard the amphibious dock landing ship USS Harpers Ferry (LSD 49) during an at-sea training evolution with the Royal Thai Navy tank landing ship Her Thai Majesty’s Ship (HTMS) Prathong (LST 715) during the Thailand phase of exercise Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training (CARAT). (U.S. Navy photo by Journalist 3rd Class Alicia T. Boatwright)

In 1956, Vice Admiral Cassady recognized that the U.S. Navy’s hope for unchallenged access to operationally significant waters was in jeopardy. A series of exercises, under the name HAYSTACK, demonstrated how effectively Soviet forces could use electronic emissions and direction finding equipment to find and fix American aircraft carriers. As a result, HAYSTACK gave rise to emission control. Initially, strike groups operating under strict emission control conditions struggled to command and control dispersed forces throughout their areas of responsibility.

Faced with greatly diminished electronic command and control capabilities [10], commanders developed creative and exceedingly “low tech” solutions. American sailors relearned the art of semaphore and visual Morse code. Helicopters developed methods for airdropping buoys containing written messages alongside friendly vessels.[11]

For the remainder of the Cold War, carrier strike groups routinely practiced emission control operations, and commanders took considerable pride in their ability to make an aircraft carrier seemingly disappear. In 1986, the RANGER participated in the multinational RIMPAC exercise. Despite the opposing forces’ best efforts to locate it, RANGER went undetected for nearly fourteen days while in transit from California to Hawaii.[12] Making this all the more impressive was the fact that RANGER continued flight operations during the transit.

The similarities between preemptive emission control and anticipated command and control warfare environments are undeniable.

Emission control training continued through the 20th century, though with less sense of urgency after the fall of the Soviet Union. Today, carrier strike groups may practice emission control operations once or twice during a work-up cycle. These events are often heavily scripted and rarely involve night flight operations. Carrier air wings undergoing graduate level training at the Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center only recently began training in a limited GPS and Link-16 degraded environment. Anecdotal feedback from pilots who have participated in these events alludes to significant challenges.[13]

The similarities between preemptive emission control and anticipated command and control warfare environments are undeniable. With small modifications HAYSTACK provides strike group commanders with a solid starting point if they wish to better prepare their sailors for future wars.

Recommendations and Conclusion

“Confidence is contagious; so is overconfidence….” — Vince Lombardi

We must not assume that future conflicts will be fought against adversaries who are incapable of challenging American technological advantages. China has demonstrated the ability to destroy satellites in orbit, and they are actively pursuing electronic attack capabilities to neutralize Link-16. These facts must be understood and accepted by commanders who have dismissed the concept of command by negation while at the same time failing to demand realistic training.

Effective command by negation demands a lucid expression of commander’s intent. Commander’s intent should focus on macro level issues and answer two questions: What is the desired end state? What will success look like?[14] Commander’s intent should not try to answer specific questions of weapons employment and target selection. Subordinates should be empowered and encouraged to use individual initiative towards achieving the stated objective. If strike group commanders and their staffs can relearn the art of operational design, and focus those efforts towards developing effective statements of intent, their forces stand a greater chance of success in a world without Predator feeds, Link-16, satellite communications, Internet Relay Chat, and e-mail. Failure to pursue this goal will only serve to maintain the status quo, which is to say deploying forces will remain unprepared to counter command and control warfare.

If the U.S. believes it remains the preeminent military force in the world, then why wouldn’t its forces train against realistic command and control warfare capabilities, assuming the implied result would be increased competence?

Quartermaster 3rd Class Alex Davis lowers a signal flag aboard the aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN 73) during a flag hoist exercise on the ship’s signal bridge. George Washington, the Navy’s only permanently forward deployed aircraft carrier, is underway supporting security and stability in the western Pacific Ocean. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Apprentice Marcos Vazquez)

Additionally, strike group commanders must demand realistic training that mimics a command and control warfare environment. It is not enough to conduct emission control exercises once or twice during pre-deployment training. Afloat training groups should own this training requirement and place greater emphasis on it during strike group training in their Composite Training Unit Exercise and Joint Task Force Exercise.[15] The Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center should consider increasing the frequency and complexity of the degraded environment training it provides to carrier air wings. Individual units must be encouraged to conduct local training sorties without the aid of data-links and secure communications.[16] Focusing on our own capabilities and how we intend to counter command and control warfare will add a layer of complexity, and therefore value, to these training exercises. If the U.S. believes it remains the preeminent military force in the world, then why wouldn’t its forces train against realistic command and control warfare capabilities, assuming the implied result would be increased competence? Ultimately, the units charged with preparing strike groups for deployment will respond to demands from operational commanders. If strike group commanders recognize their unpreparedness and demand a solution, time, money, and resources will be allocated appropriately.

While much of the #FutureOfWar discussion has centered on technological developments and innovation, we should consider whether or not this infatuation has led us down a dangerous path. Have we become so enthralled and dependent upon what is undeniably a critical vulnerability to the extent of rendering us ineffective in its absence? This is an important question to ask because, arguably, the winner of future wars will not simply be the side with the most advanced weapon systems, but likely the side who can deftly shift “back in time.”

Jack Curtis is a graduate of the University of Florida and the Naval War College. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] “Our technological advantage is a key to America’s military dominance.” President Barack Obama, May 2009.

[2] Network-Centric Warfare — Its Origins and Future. Cebrowski and Gartska, 1998.

[3] The Implementation of Network-Centric Warfare Brochure. 2005.

[4] “Inside the Navy’s Next Air War.” USNI News. Majumdar and LaGrone, January 2014.

[5] Transcript of speech delivered April 7, 2014.

[6] “General: Strategic Military Satellites Vulnerable to Attack in Future Space War.” The Washington Free Beacon. Bill Gertz. 2014.

[7] Chinese Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation publication, quoted in Gertz.

[8] Fisher, quoted in Gertz, “Chinese Military Capable of Jamming U.S. Communications System.” The Washington Free Bacon. 2013.

[9] Quoted in Hiding in Plain Sight, The U.S. Navy and Dispersed Operations Under EMCON, 1956–1972. Angevine. 2011.

[10] These diminished C2 capabilities mimic what should be expected during modern command and control warfare.

[11] Angevine, p. 11.

[12] How to Make an Aircraft Carrier Vanish. Associated Press. Norman Black. 1986.

[13] An F/A-18 pilot described the effects as “crushing” during an interview with this author.

[14] “Manage Uncertainty With Commander’s Intent.” Harvard Business Review. Chad Storlie. 2010.

[15] Composite Training Unit Exercise and Joint Task Force Exercise are the final two training events for a strike group.

[16] The United States Air Force is ahead of the Navy in this pursuit. See “Pilot Shuts Off GPS, Other Tools to Train for Future Wars.” Air Force Times. Brian Everstine. 2013.

Preparing Leaders for #TheFutureOfWar

Leveraging Communities of Practice

Recently, we tuned in for New America Foundation’s Future of War conference and watched as the military took some hits for its lack of strategic thinking, inability to work with civilian leadership, and being unable to adapt. None of these charges are new or far off the mark. As former Undersecretary of Defense Michele Flournoy pointed out, we need to reward the behaviors we want. This largely is directed at personnel and how the military develops its leaders.

To prepare for any future war, we need to reassess how we retain, educate, and promote talent. This will help us produce leaders that can think strategically and adapt to ever-changing warfare. Time matters when it comes to preserving and improving our own capabilities and we cannot afford to spend years slowly adapting to an enemy on the battlefield. While major changes to our personnel system may be forthcoming, it will take time to enact them, so we must find other ways to promote, foster, and reward strategic thinking and the peacetime practices that lead to rapid adaptation on the battlefield.

There is a direct correlation between our peacetime education and wartime adaptation. This type of education is not episodic…it is a life-long process.

In Military Adaptation in War with Fear of Change, Williamson Murray argues,

Only the discipline of peacetime intellectual preparation can provide the commanders and those at the sharp end with the means to handle the psychological surprises that war inevitably brings.

There is a direct correlation between our peacetime education and wartime adaptation. This type of education is not episodic, taking place only a few times throughout one’s career; it is a life-long process. Currently, the military is progressing in the institutional and operational domains of leader development — the professional military education and career experiences that make up the triad of individual professional development. And it is coming up short. To fight future wars leaders must be prepared across all three domains. Beyond reading lists, the various military services do very little to assist individuals in their personal study of war and warfare; individuals lack the incentives to deepen their professional knowledge on a continuous and consistent basis. There are no mechanisms like those Flournoy mentioned to reward positive behavior, let alone those that Murray argues are a prerequisite to wartime adaptation.

…the military should foster, support, and reward individual involvement in communities of practice across the profession that support a life-long study of war and warfare.

Instead of trying to develop institutional programs for life-long learning, as some have suggested, the military should foster, support, and reward individual involvement in communities of practice across the profession that support a life-long study of war and warfare. Military leaders should seek out connections with other leaders in their domain or practice to help advance individual development so that they will be prepared to adapt when the time comes.

Groups like the Defense Entrepreneurs Forum and Military Writers Guild are examples of these new professional organizations that offer the promise of strengthening the self-development domain. Although these specific organizations are new to the defense landscape, the ideas behind them are not. Etienne Wegner-Trayner, a leading researcher on communities of practice, defines them as “groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis.”[1] It doesn’t matter if interactions take place online or in person — the key is constant interaction driven by a willingness to participate. These types of networks strengthen the self-development domain in multiple ways. They provide extrinsic motivation for self-study, help individuals develop personal learning networks, and the constant interaction helps develop critical thinking skills.

Historical Precedent for Community-Based Learning

One of the first identifiable communities of practice built on the study of war and warfare began in the summer of 1801 when a small group within the Prussian military came together, and as stated by their bylaws, created an institution:

…to instruct its members through the exchange of ideas in all areas of the art of war, in a manner that would encourage them to seek out truth, that would avoid the difficulties of private study with its tendency to one-sidedness, and that would seem best suited to place theory and practice in its proper relationship.[2]

Meeting of the Reorganization Commission in 1807 by Carl Rochling (Wikimedia Commons)

The Militarische Gesellschaft (Military Society) was founded in Berlin by Gerhard Johann David von Scharnhorst and a few fellow officers to address the issue of a dogmatic adherence to doctrine and lack of professional study among its officer corps.[3] Their members included officers, government officials, and members from the academic community who met over 180 times and ultimately disbanded in 1805 due to mobilization for the Napoleonic Wars. Their weekly meetings consisted of the presentation of professional papers, book reviews, and a discussion of military related topics posed by its members; also, each year they conducted an operational analysis of a past battle.[4] In addition to their weekly discourse, they hosted essay competitions and published a professional journal, Proceedings, for its members.

The society provided a strong intellectual climate that stimulated its members’ thinking and personal development, setting the foundation for great individual and organizational achievement.[5] Its members, who included historic figures such as Carl von Clausewitz, August Neidhart von Gneisenau, and Gerhard Scharnhorst formed the core group of leaders that quickly reformed the Prussian military following its defeat at the hands of Napoleon in 1806.[6] Sixty percent of its 182 members, half of whom joined as junior officers, became generals. Five of the eight Prussian Chiefs of Staff from 1830–1870, as Prussian power grew to dominate Europe, were also members of the Society.[7]

In a similar, if more modern vein, forums like CompanyCommand and PlatoonLeader have provided an online space for company-level leaders in the Army to discuss problems, share tools, and disseminate best practices. They are communities of practice built around small unit leadership. In their book,CompanyCommand: Unleashing the Power of the Army Profession, the founders of the two websites highlight that the online space benefits individual development, “by serving as a switchboard connecting present, future, and past company commanders in ways that improve their professional competence.”[8]

U.S. Marines receive a sand table briefing before a platoon assault exercise on Arta Range, Djibouti, Feb. 10, 2014. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Erik Cardenas)

The forums also host a reading program called the Professional Reading Challenge, which gives company commanders the ability to blend face-to-face interaction with online discourse. Along with promoting reading, the program encourages members to capture their ideas in writing on the message boards. Recently, the forums added an interactive feature they call The Leader Challenge. Using video interviews of officers from deployments in Afghanistan and Iraq, forum members are presented with a real-life vignette and asked to respond with what they would do if they were in the same scenario. After responding, members are able to read others’ responses and listen to what happened in the original scenario.[9] This process allows leaders to continue to learn from a challenging event which may have taken place four or five years ago. The benefits to members are evidenced by the number of forum participants who came out on the recent Army Brigade and Battalion Commander Selection List.

The Militarische Gesellschaft along with Company Command or Platoon Leader Forums are great examples of how communities of practice assist in the development of its members by encouraging reflection, professional reading, writing, and discourse. As individuals become more active within these communities, they own self-development is strengthened.

Leveraging Communities of Practice for the #FutureOfWar

Communities of practice provide the social incentives required to stay committed to life-long learning. A small-scale study published in 2011 posited that two vital components of self-development are intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. The researcher found that recognition by mentors and peers both online and/or offline supports these motivations. As members of the profession join various communities, the social interaction provided will help them in their personal intellectual preparation to successfully lead and make decisions during the next conflict.

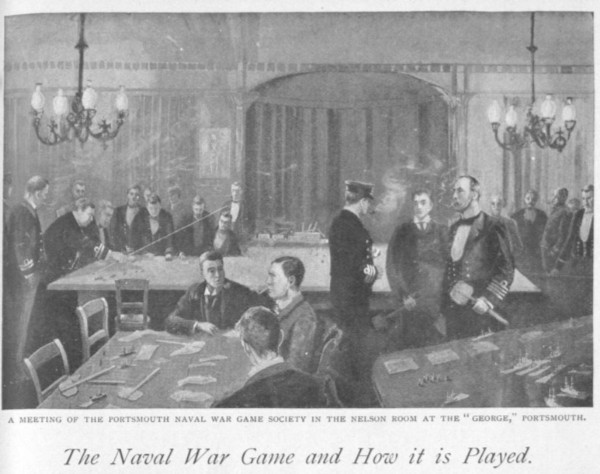

A Meeting of the Portsmouth Naval War Game Society (via Army Group York)

Communities of practice also create opportunities for individuals to develop personal learning networks. The connections made within these groups put individuals into contact with those who they can learn from on a one-on-one basis. Our own experiences validate this argument. For example, while studying at the Naval War College, I relied heavily on a personal learning network built through involvement with the CompanyCommand and Defense Entrepreneurs Forum in developing ideas and for assistance with research and writing.

The constant interaction provided by these communities help individuals develop critical thinking skills. Dr. Antulio J. Echevarria’s essay The Trouble with History, argues that many military professionals focus on the accumulation of knowledge rather than analyzing and evaluating it.[10] Many service members tend to approach reading lists with a check list mentality, instead of using them to rigorously examine concepts and past events. By exploring books and articles and discussing them in a community of practice, individuals are encouraged to move towards a more sophisticated understanding of the material, thus developing the critical thinking skills required of leaders at all levels.

While military professionals used communities of practice for centuries, the career benefits that they provided began disappearing in the Progressive Era. At this time in American history, civil service systems began focusing accession and promotion on Industrial Age mechanisms that were fairer across the personnel pool. This was meant to weed out nepotism and other class- and relationship-based influence.

Military institutions have continued to struggle with how to encourage self-development in leaders, as well as codify this development into a mechanism for career progression.

As the personnel system began to focus more on fairness than effectiveness — thereby diminishing the requirement for leadership to personally develop the leaders that would replace them — the levers used to provide benefit to self-development were removed. Military institutions have continued to struggle with how to encourage self-development in leaders, as well as codify this development into a mechanism for career progression. Our ability to prepare leaders for the development of strategy and to adapt on the battlefield is an outgrowth from these factors.

How do we leverage communities of practice and provide incentives for self-development in today’s military? This is a topic we continue to struggle with — and one we look forward to addressing in this Leadership and the #FutureOfWar series on The Bridge. If you have an idea on what is required in developing leaders for the #FutureOfWar, send us a note or submit your post to our Medium page.

We look forward to the discussion.

Joe Byerly is an armor officer in the U.S. Army . He frequently writes about leadership and leader development on his blog, From the Green Notebook. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Wegner, Etienne, Richard McDermott, and William Snyder. Cultivating Communities of Practice. (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2002), 4.

[2] Charles White, The Enlightened Soldier: Scharnhorst and the Militarische Gesellschaft in Berlin 1801–1805, (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1989), 191.

[3] Ibid., 36.

[4] Ibid., 45.

[5] While correlations between the loss to Napoleon in 1806 and the Militarische Gesellschaft are outside the scope of this article, it is important to address that prior to 1806, the Prussian military culture, organization, strategies, and tactics were all dominated by concepts inherited from Frederick the Great. This rigid adherence to tradition by the majority of the Prussian officer corps negated any of the initial benefits gained by individuals from the military society. It wasn’t until after the Prussian defeat that the society’s members moved into positions of key leadership, thus capitalizing on the relationships and education cultivated and developed prior to the outbreak of war.

[6] Ibid., 207.

[7] Ibid., 49.

[8] Nancy Dixon, Nate Allen, Tony Burgess, Pete Kilner, and Steve Schweitzer,CompanyCommand: Unleashing the Power of the Army Profession, (West Point: Center for the Advancement of Leader Development and Organizational Learning, 2005), 16.

[9] The Company Command website has a thorough explanation of the Leader Challenge at http://companycommand.army.mil/

[10] Echevarria II, Antulio. “The Trouble with History.” Parameters, Summer 1995.http://strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/parameters/articles/05summer/echevarr.pdf (accessed April 11, 2014).

“New Model” Mentoring

It began as a few Army strategists gathering around a backyard fire pit with drinks and a few cigars. This was my initiation into two key elements of strategy—scotch and cigars. As I traveled around the world, into and out of multiple conflict, and through various jobs, two things remained — scotch and cigars.

Guest Post: Addendum to “On ‘Building Better Generals’”

Guest Post: On ‘Building Better Generals’

The Center for New American Security (CNAS) recently rolled out a provocative report titled,”Building Better Generals.” There are some valuable ideas to be considered here from LTG Barno, Dr. Bensahel, Ms. Sayler, and Ms. Kidder — especially on encouraging continued education for General and Flag Officers—and I recommend you take a look at it (see also, “’Building Better Generals’ Report Rollout Panel”)