On April 8, 1904, French Foreign Minister Théophile Declassé took a telephone call from Paul Cambon, his ambassador in London. “C’est signé!” Cambon roared into the phone—”It is signed!” The modern era’s most significant treaty, the Franco-British Entente Cordiale was signed. What had been one of the world’s most significant historical rivalries from shortly after the Norman Conquest in 1066 up to that April day in 1904, was over. France and England reached agreement on a host of issues, specified and sorted out in painstaking detail through three treaties signed at once. The world would never be the same.

Political Warfare as Grand Strategy

Australia is faced with many strategic challenges. On one hand there is the rise of non-state actors, such as Islamist extremists, who aim to overhaul the Westphalian international system. Without the rule book of western nations, they combine conventional and unconventional military tactics ignoring the distinction of soldier and civilian. These non-state actors, enabled by the networked age, combine propaganda, conventional military tactics and guerrilla asymmetry, along with financial and governance structures. Whether it is Hezbollah, the Taleban, or Daesh, they utilise the entire spectrum of warfare and multiple methods to achieve their desired political ends.

Keen for a Strategy? George Kennan's Realism Is Alive and Well

...the contemporary strategic environment is undergoing a profound transition in its polarity. Obama has been placed under serious pressure to form a grand strategy that allows the U.S. to manipulate events with at will. However, a look to Kennan’s writings reveals a sense of déjà vu when reflecting on Obama’s policies.

China’s Military Strategy: Challenge and Opportunity for the U.S.

China recently published its new Military Strategy. Within this strategy China must be given credit for clearly articulating its version of the “Monroe Doctrine” for the Asia-Pacific region and its desire to no longer play second fiddle to the U.S. globally. Unlike the current U.S. national security strategy, China’s strategy is more narrowly focused on securing its near abroad (the first island chain) while also expanding its military reach to secure its interests globally. Meanwhile, the U.S. faces a complex global landscape, and must confront threats perceived and real emanating from multiple angles while managing significant fiscal constraints.

New Deal, New Strategy

The Iran Deal Heralds a Grand Strategic Decision

This past week saw the announcement of a putatively historic diplomatic agreement between the U.S. and Iran over the dismantling of the latter’s nuclear program. More precisely, the deal is a framework for a more comprehensive settlement, which will require U.S. Congressional approval (and which will provoke a storm of questions and debate, following the Senate Republicans’ well-publicized letter regarding their constitutional role).

In principle, however, the deal offers a face-saving exit from a more-than-decade-long confrontation between the U.S. and Iran over nuclear enrichment: Iran will eliminate a large portion of its stockpile of enriched uranium, dismantle most of its enrichment centrifuges, and suspend most of its enrichment program for 15 years, a verification regime (to be determined) will ensure that this takes place, and the U.S. will preside over the lifting of sanctions, theoretically subject to Iranian compliance.

The hostages disembark Freedom One, an Air Force Boeing C-137 Stratoliner aircraft, upon their arrival at the base.

Many experts — including non-Democrats — have touted the deal as a way out of the morass of Middle Eastern political rivalry in which the U.S. has been entangled since the first Gulf War. George Friedman, president of the geopolitical intelligence firm Stratfor, has argued in a recent book that the U.S. should seek a long-term rapprochement with Iran, rather as it did when President Nixon reopened relations with China, since their larger interests (including containing Sunni jihadism) overlap. This was echoed by (now former) Stratfor chief geopolitical analyst and prolific author Robert Kaplan, who argued recently that not only are the U.S. and Iran on the same side against ISIS, but that the U.S. needs a new relationship with Iran if it is to complete its “strategic pivot” to the Pacific.

If it were only that simple

However, the deal has drawn criticism, and not only from partisan quarters. In addition to opposition from Republicans, moderate voices have also pointed out serious flaws in the arrangement. The always-thoughtful John Schindler has summed up the objections quite nicely: the arrangement is unverifiable, the lifting of sanctions is permanent while Iranian compliance is temporary, and Iran has few incentives not to seek any opportunity to build a working nuclear weapon, along with ample political and ideological reasons for doing so. As a reader who responded to Kaplan’s arguments in a letter to the editor of The Atlantic noted (see Dave Esrig’s comment in the middle of the page), those hoping for a “Nixon in China” moment with Iran may have been doomed to disappointment, since Iran, compared to China during the 1970’s, does not appear as eager for an end to its conflict with the U.S. Even Iran expert Kenneth Pollack, a proponent of a nuclear deal with Iran, has noted recently that an agreement preventing an Iranian nuclear test may be the best that the U.S. can do, since Iran might prefer to stop short of such a test and settle for a “breakout window.” (Full disclosure: I studied under Kenneth Pollack at Georgetown some years ago. He will not necessarily endorse what I write here.) In other words, to quote Schindler’s article again, the U.S. “just gave Iran exactly what they wanted.” Or, more precisely, it gave it what it was probably going to take anyway.

Iran is perhaps the only state in the region (apart from Israel) that has the money, manpower, and will to fight that is needed to keep ISIS in check.

These criticisms are undeniably valid. As Pollack himself noted last year, the experience of three decades of undeclared war has depleted trust between the U.S. and Iran to the point where a deal is difficult to take at face value. Moreover, the rise of ISIS since the November 2013 temporary nuclear agreement has altered the political environment in ways that are not often remarked upon. Put simply, Iran is perhaps the only state in the region (apart from Israel) that has the money, manpower, and will to fight that is needed to keep ISIS in check. Being Shi’ite (as well as non-Arab), Iran must oppose the Sunni fundamentalist ISIS: although it is often noted that Iran keeps in touch with Sunni jihadists and sometimes uses them for its purposes, it cannot provide more than token political or material support to the larger Sunni jihadist movement, since fundamentally, they are on opposite sides of a sectarian war. No other regional state except Israel is in this position; no other regional state at all has the resources and regional influence to backstop the militias that are fighting ISIS from Iraqi Kurdistan to Baghdad to Syria to Lebanon. This is the case despite (indeed, because of) Iran’s longstanding policy of fighting against U.S. forces in Iraq, which created a triangular war in which Iran, the U.S., and Sunni jihadists are all opposed to each other — insofar as Iran wants the U.S. permanently out of Iraq, it has to take the lead in both backing its own side and ensuring that the Sunni jihadists do not make too much progress. Because of Iran’s role in containing ISIS, as long as preventing ISIS from attacking the U.S. or achieving its political goal of uniting a major chunk of the Islamic world under its rule remains the U.S.’ top regional priority, the U.S. cannot attack Iran, nor can it weaken Iran substantively; indeed, anything that in any way ties Iran’s hands works against the U.S.’ regional strategy at the moment. Until ISIS is defeated, this will not change.

Iran has warned that its armies are ready to face ISIS should they come close to their borders [file photo of Iranian Revolutionary Guards]

The effects on U.S. negotiations with Iran are predictable. In part because it is difficult to imagine a more damaging sanctions regime than the one already in place, and in part because of the nature of the U.S.-Iran relationship to begin with, the only meaningful leverage the U.S. can apply to Iran at the negotiating table is the threat of force majeure — either a U.S. strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities, or a broader war in which the U.S. would seek the overthrow of the Iranian regime altogether. Offering to pay Iran to suspend its nuclear program, as with the infamous North Korean Agreed Framework, can be presumed to be a dead letter — there would be little incentive for Iran not to pocket the goods and clandestinely proceed apace. Sticks must accompany carrots if negotiating is not to turn into begging. In the wake of the Iraq War, U.S. threats of major war against Iran rang hollow for years, but they retained a kind of surface plausibility: absent a deal, the U.S. might just be insane or desperate enough to do whatever it takes to solve the problem. Now that the U.S. is working as hard as it can to contain ISIS within the heartland of the ancient Caliphate that the latter seeks to reestablish, it cannot afford to demolish ISIS’ main enemy. Iran therefore has little to fear from the U.S. and less incentive to abide by a deal. (Or even to make one. The fact that the U.S. has recently humiliated itself by setting a deadline for making a deal, while Iran felt no such pressure, speaks for itself.)

…the U.S. twin goals of counterterrorism and counterproliferation work against each other in the Middle East.

Unsolvable dilemmas

However, there is an insoluble policy dilemma at work. As I have written before, the U.S. twin goals of counterterrorism and counterproliferation work against each other in the Middle East. Counterterrorism — really, countering the global Sunni jihadist movement in any of its serial forms — requires the U.S. to adopt a number of policies. It must support and strengthen established states (which, ipso facto, cannot abide more than a minimum of internal violence from organizations dedicated to their overthrow), support ethnoreligious constituencies that are immune to co-option by the Sunni jihadist movement (particularly the region’s Iranian-backed Shi’a communities, but also other groups), and, where practicable, avoid putting its troops where jihadists can score easy victories by targeting them. All of the above require cooperation not only with Iran, but with a host of other regional actors, many of them malodorous. (This includes, as U.S. policy makers have recently discovered, Syria’s ‘Assad, since Syria’s Sunnis were vulnerable to cooption by ISIS in a way that its other ethnic groups are not.) It also, sooner or later, puts the U.S. in the position of, at minimum, having to distance itself from Saudi Arabia, whose founding religious ideology, Wahabism, is an extreme form of the Salafism that motivates Al Qaeda and ISIS, and which, since the rise of Al Qaeda, has benefited from foreign wars that can draw off Saudi extremists who might otherwise attack home soil.

Iraq, previously, provided this outlet; the war against ISIS is merely a continuation of that conflict. At maximum, countering Sunni jihadism requires politically opposing Saudi Arabia, ultimately by waging a proxy war against it. (Saudi Arabia is widely accused of supporting ISIS via “private” contributions to Islamic charities and aggressive proselytization of Wahabism.) Counter intuitively, countering Sunni jihadism even strains the U.S.-Israel relationship, since Israel has always feared states more than terrorists and since Israel’s primary adversary is Iran while its sometime partner against Iran is Saudi Arabia.

The U.S. is on the verge of batting zero for two where this dilemma is concerned….the U.S. must now make the best of what few options it has left. It is in light of all this that we must assess the Iranian nuclear deal.

Counterproliferation, on the other hand, requires just the opposite. Because, for those who seek them, nuclear weapons are the ultimate security guarantee, and because the dismantling of a nuclear program is so difficult to verify, it is very difficult to disincentivize their production once a state decides to have an arsenal. This necessitates that the U.S. be open to the policy of waging war against would-be proliferators (or threatening war, which amounts to the same thing), often with incomplete evidence of their own activity — witness the neverending controversy over whether it was worthwhile to oust Saddam Hussein, who had no nuclear program butappeared to, and who did possess raw uranium ore. Such wars are not only bloody and expensive, but also disruptive: as in Iraq, they create ungoverned spaces where Sunni jihadists can first take refuge and then take power. On the other hand, smashing would-be proliferators is in line with Israeli policy goals and therefore helps, rather than hinders, U.S.-Israeli cooperation. Such wars and threats of wars also work to the advantage of Saudi Arabia, in the same way that countering ISIS and its predecessors has worked against Saudi policy goals, and also because they (ideally) eliminate potential nuclear threat close by.

The U.S. is on the verge of batting zero for two where this dilemma is concerned. Having destroyed Iraq, it created a vacuum that is now controlled by ISIS and used as a staging area for attacks that will probably one day seek to destroy Jordan in preparation for assaults on Jerusalem and Mecca. On the other hand, having avoided going after Iran when it had the chance, the U.S. is now in no position to stop Iran from obtaining a nuclear arsenal, and, in turn, creating the potential for a regional arms race. Almost all of this involves choices already made; the U.S. must now make the best of what few options it has left.

Uneasy ground to walk on

It is in light of all this that we must assess the Iranian nuclear deal. A few points now seem obvious, points that do not fit easily into the dominant narratives surrounding the issue.

…the U.S. must pick not only its policies, but its problems.

First, counterterrorism really does reign supreme. The U.S. has more to fear, for its purposes, from Sunni jihadists than it has from Iran, and for that reason it will need to abstain, at the very least, from getting in Iran’s way as it kills them off. This may or may not make a deal on Iran’s nuclear program desirable, but it does argue for tabling the issue one way or the other.

Secondly, for that reason, the critics who noted that an Iranian deal would herald the end of U.S. counterproliferation policy in the Middle East are right. The U.S. does not have the money, the troops, or the political will to continue enforcing the nonproliferation regime in the Middle East. It does not have the money because of its economic slowdown and demographic problem: if the U.S. is to avoid serious fiscal problems in the coming decade, it will have to adjust its domestic spending programs, and it is not possible for either party to take a serious position on this while pouring funds into a Middle Eastern war of choice. (To this day, a politically devastating but substantively irrelevant talking point against entitlement reform in the U.S. has been that the U.S. had a trillion dollars to throw away on Iraq, but cannot find the money to pay for Social Security and Medicare.) It does not have the troops because enemies are arising in other quarters. Not only will the U.S. sooner or later have to complete the “strategic pivot,” as Kaplan notes in the above-cited article, but the U.S. will also need troops to deter Russian aggression against vulnerable NATO members such as the Baltic states. It will also need to cease relying on Russia for logistical support to operations in near-inaccessible parts of the greater Middle East, for obvious reasons. Given all this, tying the U.S. down in a Middle Eastern land war should not be considered an option at this point. As for political will, the U.S.’ political polarization of late is well-known, and until it can be solved it will pay to adjust expectations accordingly. For all these reasons, the U.S. will have to take whatever deal it can get that will allow it to leave the Middle East to its own devices, and make do with the resulting consequences.

Thirdly, the U.S. is in the midst of a smaller policy pivot within the Persian Gulf. Assuming it does not deviate from its goal of rolling back ISIS in any way possible, and assuming it needs Iran’s help for these purposes, the U.S. will eventually back away from its relationship with Saudi Arabia even as it seeks a new relationship with Iran. The U.S., to paraphrase Lord Palmerston, does not have friends in the Middle East, only interests — and Saudi Arabia’s goals are no longer those of the U.S.

And fourth: the U.S. will have a different relationship with Iran from here on. Not only will the U.S. have to adjust its policy to deal with ISIS, but it will have to adjust its policy to deal with the wider geopolitical situation. With the U.S. once again in a confrontation with Russia, it will have to start treating Middle Eastern issues as relatively peripheral once again, and for that reason it will have to begin treating its Middle East goals as a means to a larger end rather than an end in itself. In the Cold War, the U.S. pursued relationships of convenience with Middle Eastern states to prevent them from falling completely into the Soviet Union’s orbit. The Iranian deal could be the first step toward something similar. Although Iran is seen as falling into Russia’s political orbit of late, this is in part due to U.S. opposition to it, while, conversely, and as noted, the U.S. has increasingly little to gain from rigid adherence to the regional partners it does have. Separating Iran from Russia — not by making it an ally, but by making it unaligned — should be a U.S. policy goal at this point. The model is Nasser’s Egypt during the Cold War, which was emphatically not pro-U.S. but was kept from being unambiguously pro-Soviet. An Iranian nuclear deal will open up opportunities in this area. U.S. expectations should be modest: Iran will not necessarily do what the U.S. wants, but the U.S. can prevent it from becoming too much of a thorn in the U.S.’ side as it confronts Russia.

Finally, there will be more to do on broader policy questions. Partnering with Iran against ISIS will only work if the U.S. is willing to put considerable political and military muscle behind that effort, even allowing for a prohibition on introducing U.S. ground forces. Attempting to separate Iran from Russia will only be worthwhile if the U.S. deems protecting its NATO allies to be important and does what it takes to do so. There will be regional political fallout in the Gulf which the U.S. will have to manage, often aggressively. In other words, this is only the beginning.

However, the U.S. must pick not only its policies, but its problems. The U.S. has an opportunity to walk away from a resource-sapping Middle East counterproliferation policy, and it is advisable to take it. There does not seem to be much of an alternative.

Martin Skold is currently pursuing his PhD at the University of St. Andrews, with a dissertation focused on the strategy of long-term security competition between states.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

The "Islamic State" and the #FutureOfWar

Why They Are a Junior Varsity Team

When asked about the “Islamic State” last year (then referred to as ISIS), President Obama stated that, “if a jayvee team puts on Lakers uniforms that doesn’t make them Kobe Bryant.” After the Islamic State swiftly overtook Mosul and much of western Iraq last summer, media pundits and politicianscriticized the analogy. This essay argues the opposite, President Obama was absolutely correct in referring to the Islamic State as a “JV” team, and how policy makers conceptualize the world order and its threats has enormous implications for the future of war.

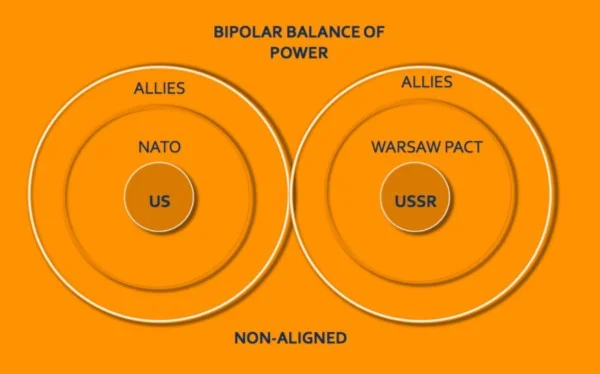

In order to conceptualize the future of war, one must understand the strategic setting (or world order). Nearly two decades ago, Barry Posen and Andrew Ross offered competing visions for U.S. national security by offering a typology for U.S. grand strategy, each with a preferred world order[1]. Instead, this essay suggests that grand strategy is not the driver of world order, but rather world order is the driver of grand strategy. Each strategic setting constructs a different type of world, with different centers of political, military, and economic power. The three scenarios in this thought experiment are: bipolarity (two antagonistic superpowers), unipolarity (one superpower) and multipolarity (multiple regional powers). These poles represent a “center of gravity” that strong nation-states generate with the weight of their economic, political and military systems.

…grand strategy is not the driver of world order, but…world order is the driver of grand strategy.

Scenario 1: Bipolar World

Neorealists such as Kenneth Waltz and Robert Art argue that the bipolar world order is the most stable. According to the neorealist literature, bipolarity tends to be the preferred world order from the U.S. security perspective because total war is unlikely between two nuclear-armed states, and only a nuclear-armed state can rise to superpower status. Instead, wars in bipolar worlds are typically proxy wars fought on the edges of hegemonic influence. The proxy wars of the Cold War, most notably the Soviet incursion in Afghanistan and the U.S. incursion into Indochina, are typical of wars fought in a bipolar world. One superpower intervenes abroad, outside their sphere of influence, and the other tries to undercut their actions. If China were to emerge as a peer competitor this century, the U.S.’s ‘Pivot to Asia’ is a logical security strategy, as most of the proxy wars with China are likely to take place in the Pacific theater of operations (but not in China itself).

Conceptualization of a Bipolar Strategic Setting

One characteristic of a bipolar world order is that it gives smaller players on the world stage an alternative to the U.S. for alignment and security assistance. For instance, during the Cold War, Egypt balanced U.S. influence by alternating between Moscow and Washington for political sponsorship, military training, monetary benefits and arms procurement. If China, or even Russia, rises to the level of a peer-competitor, “mercurial allies,” such as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) would be faced with a choice: either align with U.S. interests when seeking security assistance, or seek assistance from the other superpower.

Scenario 2: Unipolar World

The sun never set on the British Empire. (Wikispaces)

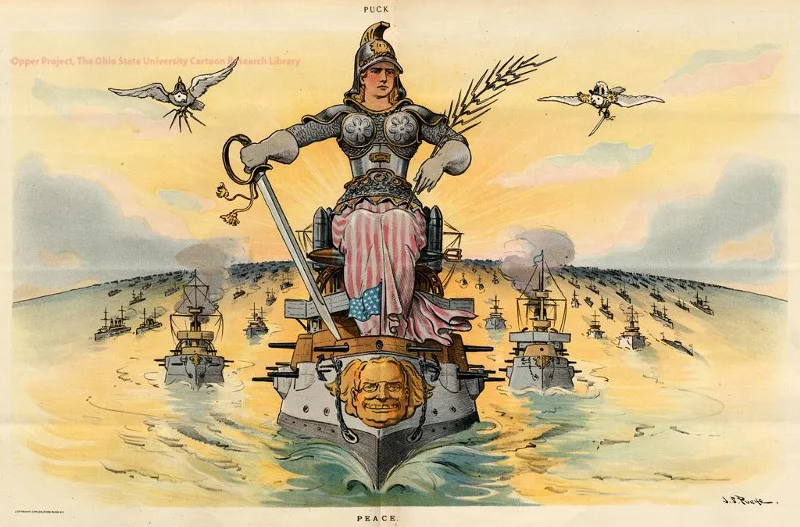

In the unipolar world, a single hegemon drives the world order, much like the Roman or British Empires did at their heights. Given the vast economic and military power of the U.S., some analysts suggest the global order for the next several decades will be unipolar. Certainly this was the general consensus after the collapse of the Soviet Union a quarter century ago. In this scenario, strategically speaking, the U.S. will have to resolve a major incongruity in the national political-military culture: distaste for imperial behavior, yet the desire to expand commercial enterprises and protect human rights abroad. Likewise, U.S. strategists will have to face an inherent paradox: every nation-state resents the hegemonic superpower, but every nation-state is seeking to become the hegemonic superpower.

The U.S. will have to resolve a major incongruity in the national political-military culture: distaste for imperial behavior, yet the desire to expand commercial enterprises and protect human rights abroad.

In this scenario, as the unipolar power, the U.S. will be called upon to intervene in regional conflicts. Without a clear national security strategy, U.S. policy makers will pick and choose battles in an ad hoc manner, administration by administration, driven by short-term political agendas. Yet, U.S. actions abroad will have unseen second and third order effects that will endure for decades and even centuries to come.

The realist would argue that as the unipolar power, the U.S. will naturally desire to retain supremacy and contain any potential peer competitors. Therefore, expansion of NATO and security of the Pacific would drive national strategy (consciously or not): NATO to contain a revisionist Russia and military presence in the Pacific to thwart Chinese aggression.

In this scenario, the U.S. can also intervene in smaller regional conflicts at will. But, what kinds of conflicts does the superpower face in a unipolar world? These are the same types of battles faced by the Roman and British Empires, and much like bipolar scenario, they will take place at the edge of the hegemonic influence. So, you can expect the U.S. to become involved in smaller regional conflicts around Russia’s borders, between Turkey and the Middle East, and around the Mediterranean and Pacific Rim.

Scenario 3: Multipolar World

In a multipolar world, there is no single superpower. Interdependence and transnational interests cloud the traditional notion of the “nation-state.” And, without strong nation-states to hold players accountable, there is a very high threat of everything from nuclear proliferation to cyber attacks from rogue organizations. Furthermore, cooperative security arrangements through multinational institutions mean priorities shift and change all over the world, all of the time.

...without strong nation-states to hold players accountable, there is a very high threat of everything from nuclear proliferation to cyber attacks…

A political realist could argue the emergence of the Islamic State today is a direct reflection of the fallout from a lopsided world order. Without Russia and the U.S. aggressively supporting the nation-state system and propping up regional powers, ungoverned spaces are left in a turbulent security vacuum. And, in an ominous foreshadowing of future events, Posen and Ross suggested “the organization of a global information system helps to connect these events by providing strategic intelligence to good guys and bad guys alike; it connects them politically by providing images of one horror after another in the living rooms of the citizens of economically advanced democracies”[ii].

According to Posen and Ross, a multipolar world begets multilateral operations. The U.S.’s contribution to military operations are typically where they have the most significant comparative advantage: aerospace power. Therefore, the future of war in a multipolar world sees the U.S. leading air campaigns against shifting enemies, mainly in failed states. Not only that, the U.S. will aggressively seek to maintain their comparative advantage in aerospace power.

Realists argue the multipolar world is the most chaotic. First, without a strong superpower to support smaller nation-states, smaller players cannot maintain a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. Weak and failed states tend to spew a plethora of competing factions, some with nefarious intentions. Second, the aggressors are unclear. Some factions are supported by regional hegemons, and others are simply trying to fill the power vacuum. Finally, the U.S.’s reliance on aerospace power makes U.S. forces even more vulnerable to asymmetric attacks. The non-state actor is unlikely to strike using conventional methods, so the battlefield is cast with ambiguous players, many of which are supported by regional hegemons.

Conclusion

*Quasi-nuclear denotes states with nuclear aspirations or undeclared nuclear capability

It is difficult to discern which world order is preeminent now, but it is possible the three world orders are not mutually exclusive, nor are they static conditions. Without a doubt, the U.S. has the world’s strongest economic and military systems, which suggests they are the lone superpower. Despite this, the world is actually experiencing many of the consequences derived from a multipolar world order. This is especially prominent in the Middle East, where regional hegemons are not officially nuclear states (although several of them have the capability and will to go nuclear). So, perhaps the best way to conceptualize the world order is unipolarity in locations closest to the U.S. and elements of multipolarity in distant locations with regional hegemons. Despite their differences, unipolarity and multipolarity both suggest that the future of war will be fought on the fringes of U.S. influence, against smaller and more agile adversaries- some of which have the ability to strike the U.S. homeland, many that are getting support from a regional hegemon, and most of which are the excrescence of a failed state. This is exactly why the Islamic State is a “JV” team. At this time, the Islamic State neither has the resources nor the capability to achieve the hegemony that comes with nuclear power and projection; they are simply a satellite of a larger hegemon. The U.S.’s response to the Islamic State typifies the future of war in a multipolar world: broad coalitions and the use of aerospace power against disparate organizations.

…the future of war will be fought on the fringes of U.S. influence, against smaller and more agile adversaries…

The main issue for U.S. policy makers is not from the chaos surrounding terrorist organizations like the Islamic State. Too much time and attention has been placed on this foe while ignoring much more important issues. For instance, global conditions are going to force the Department of Defense to place the primacy on maintaining air superiority, yet many conflicts of the near future will require the techniques of agile, flexible, and rapidly-adaptable fighters. It is very important to have a force structure designed for the threats it will face. Another issue will be how the global balance of power shifts if Iran, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, or Israel becomes a declared nuclear state. If just one of these states goes nuclear (officially), it is highly likely to set off an arms race in the Middle East. More importantly, recent incursions into Crimea and Ukraine demonstrate that President Putin is intent on implementing his revisionist agenda. Given that Russia is a nuclear power and the proximity of Ukraine to NATO allies, this is the biggest threat to U.S. security interests. But, even more dramatic and uncertain will be if a non-state actor is to acquire a nuclear weapon. U.S. policy makers will no longer be dealing with a JV team if the Islamic State (or any other terrorist organization) was to obtain a “loose nuke.” To use a sports analogy, it will be the equivalent of a JV high school basketball team having LeBron James in the starting lineup: they are probably going to win a few games against older and more experienced teams.

Diane Maye is a former Air Force officer, defense industry professional, and academic. She is a PhD candidate in Political Science at George Mason University where she studies Iraqi politics. She is a proud associate member of the Military Writers Guild. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Posen, Barry and Andrew Ross. “Competing Visions for U.S. Grand Strategy” International Security 21:3 (Winter 1996/7): 6.

[2] Ibid, 25.

Leadership by Example Requires You to Roll Up Your Sleeves

Jeong Lee’s article “A Case for A Sustainable U.S. Grand Strategy: Retirement without Disengagement for a Superpower” advocates for the United States to adopt the “role of exemplar over that of crusader” to rejuvenate its national strength and to bolster its legitimacy abroad. Lee goes on to encourage a U.S. grand strategy that focuses on homeland security, because “setting one’s house in order does not necessarily mean isolationism.”

However, the argument for a reduced or “retired” role for the United States is not new and is often broached in times of fiscal constraint and more often after completing ‘adventures’ overseas. The failure in most of these arguments is to expect it would be in the interests of the rest of the global community to maintain the peace and rule of law established by America’s engagement. To be a leader in the world, the United States must not “retire” and pass the responsibility entirely onto our partners, but instead roll up our sleeves and work alongside our partners to defend international norms.

In short, the American commitment to new horizons for ‘happiness’ does not die out, it is rejuvenated by each new generation and adapted to their times.

Since the birth of the United States, a key goal of our foreign policy has always been to ensure market access (or free/open markets) and uphold the rule of law to support our economy. In the Declaration of Independence, our forefathers called it “the pursuit of happiness.” In the Monroe Doctrine, it was stated as the “United States [shall] cherish sentiments the most friendly in favor of the liberty and happiness of their fellow men.” Before World War II, the Atlantic Charter phrased it more directly: “all states [shall have equal access] to the trade and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity.” After World War II, in Secretary of State George C. Marshall’s address at Harvard University in 1947 advocating for theMarshal Plan he reaffirmed that “the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace.” In short, the American commitment to new horizons for ‘happiness’ does not die out, it is rejuvenated by each new generation and adapted to their times.

Back in the present, Lee suggests “the United States should first withdraw its military presence from both” the Middle East and East Asia for two different reasons. On the one hand, as Toby Jones argues in his 2011 Atlantic piece“protecting the flow of oil from the Persian Gulf to global markets is far less necessary than it once was” since the world has plenty of oil. This ignores the fact that oil is a globally traded commodity and the U.S. would still be impacted if events reduce oil production anywhere around the globe.

And the other reason for withdrawal? “A continued U.S. military presence may not be necessary because Taiwan, Japan and South Korea are fully capable of defending themselves without U.S. military aid.” Even though reports from East Asia show the contrary with the debate on Taiwan adopting a “porcupine strategy” to raise the cost of a Chinese invasion, Japan is ‘militarizing’ because they want to be able to defend themselves in case the United States is committed on another front, and South Korea has continued to delay taking over wartime leadership. ‘Retiring’ from these regions could lead inevitability to destabilization and by passing the security responsibility to local allies the United States would be interpreted, by friend and foe alike, as retreating.

The world faces many challenges, and if the United States ‘retires’ to our corner, there is little to be shown that others will be able to maintain the peace.

After the removal of U.S. forces from the Middle East and East Asia, Lee argues that “the United States Armed Forces should reorient their focus towards homeland security.” It goes on to say with the cost savings from reduced global military presence “the United States [should] bolster its homeland security apparatuses to counter the threat of terrorism at home. And the U.S. can contain threats posed by non-state actors through multilateral police action with the cooperation of its allies.” There is always an argument for the savings from reducing U.S. global military presence to be used in other areas to benefit the greater good. The reality, however, is our partners and allies are not just asking for more FBI agents in the fight against terrorists — they are asking for even more U.S. military engagement in Iraqand now Libya. The world faces many challenges, and if the United States ‘retires’ to our corner, there is little to be shown that others will be able to maintain the peace.

‘Retirement without Disengagement’, is summarized as a renewed focus on “diplomacy to accommodate [U.S.] admirers as well as its rivals.” Because “the fewer wars the United States fights, the more money and lives it will save. Even better, the fewer wars the United States fights, the more likely the global community will appreciate its restraint and sober humility with which it approaches relations with other nations.” Diplomacy should always be our first option, though there is a difference between fighting less and retiring from the world.

Unfortunately, our near-peers and rising powers have shown they will test how far they can stray from the U.S. backed liberal world order. They are trying to see if they can replace the U.S. system with a world order more in their favor without going to war and risking total economic ruin. The ‘retirement’ case highlights the need for greater focus on diplomacy and a reduced role for the U.S. Armed Forces, but it is suggesting an over-correction; the risk is going too far towards irrelevance while passively hoping that we have been a good enough of an example to others who might pick up the burden of protecting the international order. Our history — and common sense — shows that if we expect others to fight for the pursuit of happiness, we must be there alongside our friends doing the work.

Leo Cruz, is a former U.S. Naval Officer who served in Operation Iraqi Freedom and a Partner with the Truman National Security Project. The views expressed here are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. military or the Department of Defense.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

A Case for A Sustainable U.S. Grand Strategy: Retirement Without Disengagement for a Superpower

...the discussion of U.S. grand strategy by both the neocons such as Robert Kagan and liberals such as David Rothkopf seem to be bereft of proper geostrategic contextualization due to fervent dogmatism, and is out of touch with today’s geopolitical realities. Part of the absence of nuanced contextualization can be understood in light of the fact U.S. foreign policy and its grand strategy are grounded in the ahistoric inclinations of its citizens.

![Iran has warned that its armies are ready to face ISIS should they come close to their borders [file photo of Iranian Revolutionary Guards]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5497331ae4b0148a6141bd47/1448826383107-16PDKQFKLJ1JV7WNJ7SN/image-asset.jpeg)