Millennials are on track to make up nearly fifty percent of the workforce by 2020. That is to say, they represent the future of the U.S. military. While the military should not change its core character or values to accommodate Millennials, it should recognize their views of the world differ from those of past generations. While Millennials present some new training and leadership challenges (getting them off their phones, for example), they also offer a way for the military to advance into the modern world at the ground level.

Friction and ISIS

Daesh is now meeting what Clausewitz refers to as friction in war, i.e., those factors that sap the war machine of its vitality. In its drive to establish an Islamic Caliphate, Daesh reached out far and wide to project its influence, overextending its capabilities in the process. The developing stalemate across its fronts could indicate an operational pause to consolidate, or it could simply mean that it is reaching the “diminishing point of the attack.” For an organization that sells itself as a dynamic, maneuver-oriented offensive force, Daesh cannot afford to get locked into a defensive war of attrition.

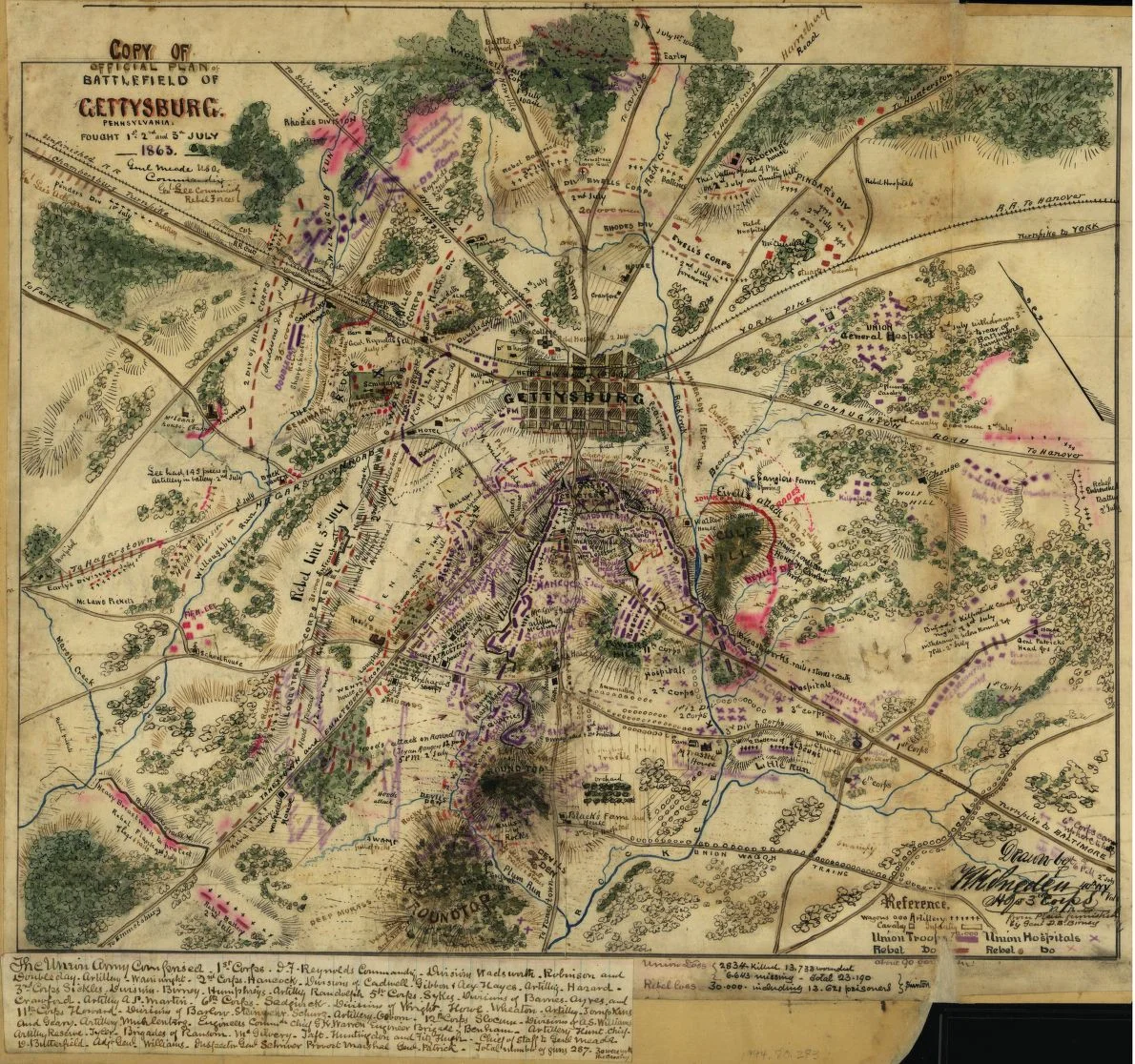

Leadership Lessons from Gettysburg

Military leadership comes in all different forms. It can be embodied in the leadership of troops on a battlefield, or it can occur behind the scenes in moments no less important. The Army defines leadership as influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to improve the organization and accomplish the mission. These bland, doctrinal terms are best brought to life in the form of historical vignettes, a valuable tool for teaching the process of leadership.

The Treaty of Paris: Negotiating from Weakness

Cyber and the National Guard: A Strategic Trust

Threat drives technology. This has been the case for the U.S. military for the last 150 years. One could say that forecasting what the next threat will be is actually what drives technology. Two prime examples of this are coastal and air defenses of the United States in the beginning and middle of the 20th century. Now we are facing an ever-developing threat: cyber attacks against our nation’s infrastructure. These are becoming more invasive and dangerous to our national security, given how much a modern military relies on cyberspace for communication and command and control.

Decision Point: The Challenges of Leadership in Battle

Imagine that you are a battalion commander and that you find yourself in the following situation. You have command of an understrength US Army infantry battalion (350 men) and are defending a small rocky outpost with very little support from friendly troops on their right. You are the decisive operation on the left flank and so have zero support from the left. Rocky terrain and steep elevations will not allow for any fire support to be brought to bear on your position, meaning that you have only the battalion’s organic weapons to defend yourself. A five-day patrol has led you to this position, so you are close to running out of water and food.

All Hell Broke Loose: The U.S. Army and OPERATION TOENAILS

Few people, save avid students of the U.S. war in the Pacific, have ever heard of the small island group called New Georgia. Yet, in the summer of 1943, the island was the scene of some of the most brutal fighting of the entire war. It was on New Georgia where the 43rd Infantry Division experienced the highest number of cases of neuropsychiatric casualties (variably known as combat fatigue, shell shock, war neurosis, or post-traumatic stress disorder) casualties in any division during one operation in the entire war. For two of the three Army divisions on New Georgia, it was their baptism of fire, and one that they would never forget. While the capture of New Georgia was vital to the strategic and operational success of the Solomon Islands Campaign, the battle itself is a supremely interesting study in small-unit tactics, joint Army-Navy operations, logistics operations, and the trials of a joint command.

The Specialist Speaks: #Reviewing “Thank You for Being Expendable”

Navigating by Terrain Features

How the Army Sees Itself in History

In land navigation, there are several different ways to negotiate map reading and get from point A to point B. You can use a magnetic azimuth to go from point to point, but that often means that you have to stay on one path the entire time regardless of how difficult the terrain is. It is a very rigid and time consuming approach. Another approach is called navigation by terrain features. The navigator uses their knowledge of map-reading to pick out significant terrain features on their way to and at their destination. Then they follow those terrain features, such as hills, valleys, roads, or buildings, to their destination. This method of navigating can be less stressful and occasionally less accurate but quite often the most successful.

When the Army, and by definition those in it, looks at its history, it tends to reflect on its own significant terrain features, i.e., wars. Even the way that colleges teach U.S. history is done via the idea of wars as a benchmark. To be sure, for a military, war is our Super Bowl. It’s where we try out our doctrine and strategy, refine our procedures, and, hopefully, come out with a win. It is only natural to use war as a significant terrain feature.

It is only natural to use war as a significant terrain feature.

The problem, though, is that history does not stop between wars. Indeed, sometimes what wins wars are the reforms that take place in inter-war periods. While it is sometimes tempting to skip over the boring periods, those often contain gems that can help us relate to our own time. For example, I recently wrote a white paper on the history of my National Guard’s force structure that demonstrated that the most radical changes to force structure happened during periods of peace, not war. These decisions reflected changing threats, technology, and doctrine and shaped the force that we have today.

While doing research, I came across an edition of the now-defunct “Coast Artillery Journal,” of the even more defunct Coast Artillery Corps. This Corps was in existence for barely fifty years from the beginning of the 20th century. The edition of the journal I was reading was from 1922 and was an incredible snapshot of both the Corps and the Army at the time. The post-World War I Army was experiencing both growing and shrinking pains. Growing, from the vast experience the Army had gained from the war, and shrinking, from force structure cuts.

From new technology to book reviews to leadership studies, the journal embraced their cause as a profession and encouraged their officers to write about it. To me, this echoed the present movement to engage military officers to begin writing about their experiences, thoughts, and solutions.

“Of the two hundred and five documents on the official list of War Department publications, not one touches on leadership.”

Of note was an article on leadership, where the author, a lieutenant colonel, notes that “of the two hundred and five documents on the official list of War Department publications, not one touches on leadership.” That is a damning indictment of an organization that calls itself a profession since 1880. We now have enough manuals and publications on leadership to build a small mountain (although we continue to face many of the same perennial challenges in leadership) so it is clear that we are making strides.

Budgets, the ever-present monster to the Department of Defense, were an issue at the time, as the journal included a very innovative piece on how to use a M1903 Springfield rifle on a to-scale terrain model as a miniature direct fire range. It even included such details as a raised platform simulating an aerial observer. This is the kind of adaption that sharing ideas and promoting an innovative culture can bring about.

The journal also ran an editorial on the recent force structure reductions that the Army was facing. In a statement that could have been easily run in “Stars and Stripes” today, the editor writes,

“For my part I think it would be a wise thing if the army went quietly about its business for the next few years, sought every proper means of showing its own inherent worth, both to government and the people, cleaned its house wherever necessary, both in personnel and in customs, and then found itself ready to take advantage of the turn of the tide. And the tide will surely turn.”

The Army of 1922 was not part of a cultural terrain feature yet it warrants studying. If we are going to “turn the tide” of our own political and economic storm, we should not attempt to re-invent the wheel. It might behoove leaders and historians alike to look away from the dramatic terrain features of history and instead examine some of the paths less trodden. As Robert Frost says, “I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.”

Angry Staff Officer is a first lieutenant in the Army National Guard. He commissioned as an engineer officer after spending time as an enlisted infantryman. He has done one tour in Afghanistan as part of U.S. and Coalition retrograde operations. With a BA and an MA in history, he currently serves as a full-time Army Historian. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Operational Reserve on Burnout

While all National Guard units have a small full-time staff for planning and handling day-to-day functions like armory maintenance, the commander and first sergeant, as well as platoon leadership, are the ones who drive future planning. Company leadership gets so tied up in paperwork and requirements that they are barely able to get out and see how their company trains. This is precisely the opposite of how it is supposed to be. This hits commanders the hardest. Commanders have to spend at least twenty to thirty hours a week engaged in National Guard business, and that’s on top of their normal job requirements. Obviously, this is not sustainable. Guard units are still deploying, as much as this is not highlighted on the news. Mobilization tempo has dropped, but not disappeared. Guard leaders are still as busy as ever, doing more with less.

#Professional Warfighters

A Historical Perspective on the so-called “Profession of Arms”

An on-going discussion at the Strategy Bridge on the topic of the Army as a profession got me thinking about the general idea of the “profession of arms.” Naturally, I immediately did two things: 1) Looked in the mirror and asked, “Do you even profession, bro?” and 2) Thought of historical precedents, as I always do when posed a quandary. Because of course I want to say that I’m a professional; as an Army officer, it’s like the kiss of death to my career if someone calls me unprofessional in an evaluation. And what would that mean for everyone’s favorite buzzphrase, “Officer Professional Development?” If we’re not professionals, then how do we do OPD (I don’t think most people do it, but that’s another story)?

Bottom line, the Army preaches professionalism ad nauseam but seldom bothers to ask the question of what professional warfighting organizations have looked like in the past. Which leads me to ask…

Most ancient and early-modern wars were fought with unskilled warriors, who relied on mass and fear to overpower their enemies.

What does a professional warfighting organization look like? Well, man has gone to war since the…um…pretty much always, according to archaeologists and historians. Most ancient and early-modern wars were fought with unskilled warriors, who relied on mass and fear to overpower their enemies. The real transition is when a society appoints a certain section of the population to learn war and practice it, for the general good. There have been several instances in history where these professional armies have developed. First off, we have…

Sparta

On the Grecian islands, the city-states developed tiny armies based around the phalanx formation (lots of dudes with pikes and shields forming a tight mass), where warfighting became phalanxes pushing each other around the battlefield until honor was fulfilled, and then they’d go and polish off a few amphorae of wine over the few guys who managed to get themselves killed. Sparta really messed this up for everyone by essentially creating a slave-based economy to support a class of warriors who brought killing into fashion again. Their tactics were designed to destroy the enemy’s phalanx and turn it into a death trap. The mark of a professional soldier is training, and man, did Spartans train. Not only did they train, they built a culture around being good at killing people. The problem became that the other city-states caught onto this idea, too and professional armies began popping up all over the place. Warrior-culture became the vogue (not unlike all things Spartan these days, except for the whole slave thing) and Sparta got out-manned and overrun.

Not pictured: The abuse of children and mass slavery. But sure, call your platoon the “Spartans.”

The whole thing didn’t end well for the Grecian world, as when you make a name as the toughest kid in the neighborhood, all the other tough kids will come gunning for you.

Rome

The next kid on the block to up the ante on professional warfighting was Rome. Rome basically took the Spartan model, added combined arms, the idea of a Republic (ideals beyond the warrior for the warrior to fight for), a set period of enlistment, and a pension. Worked out pretty well for them; Roman legionaries were some of the best soldiers ever seen on the planet, as evidenced by an empire that ran from Britain to Persia. They had organized training, a robust non-commissioned officer corps (the sign of any good army), and a developed force structure (legions). Legionaries could serve their twenty years and retire to a piece of land in the newly conquered territories. Or they could die in battle versus these crazy Germans who kept attacking the frontier. Yup, over-expansion killed the Roman Empire even as its legions fought each other in civil wars. Not a pretty way to go.

"I can’t wait to get my twenty year papyrus…"

Medieval Warfare

So after the Roman Empire fell, warfare veered towards the dude who brought more dudes on horses to the fight. It was the era of knights in shining armor, or, more accurately, knights in really heavy armor on big, armored horses, who would plow right through the enemy, causing massive blunt force trauma, decapitations, etc. Not the prettiest era ever. But for hundreds of years, the mounted horseman ruled the battlefield. Now horses and armor aren't cheap, nor is fighting on horseback easy, so a new class of warriors developed. Knights gained prestige through combat, and pledged their loyalty to the monarch, or lord, or whomever would toss them the biggest bag of gold. Ethics were attempted through the chivalric code, but that usually went out the window at the first drop of a coin. Knights became landed, because to have plentiful horses, you must have plentiful land. This tied medieval warriors down to one place and allowed for the great tradition of feudalism to begin. Knights were professional soldiers to the extent that their entire lives were essentially lived under arms, or at least, that was the original point. They would eventually become an upper class elite society, who would be shocked to meet the next level of professional soldier…

Swiss Mercenaries and the Landsknechte

By the 1500s, the pike and the crossbow had pretty much relegated knights to a supporting combat role. Monarchs had to protect their horsemen, because knights were doggone expensive and losing one on the battlefield took time and money to replace. In fact, cost was becoming an issue for everyone. The little Ice Age and the Plague had really done a number on Europe’s population. Leaders still wanted to fight each other but weren't sure they had the population to support war and the economy at the same time. Italy and Spain solved this problem by hiring German (Landsknecht) and Swiss mercenaries to fight their wars for them. These guys were good. Well, at war at least.

Landsknechte relied on massive two-handed swords, pikes, and beautiful music to rout their enemies.

While essentially immoral and dissolute (“rape, pillage, and plunder” was a phrase they kinda coined), they excelled on the battlefield. They turned war into their full-time profession. All they did in life was go to war for the man with the biggest pocketbook. And for the monarch, it was usually more than worth it. German and Swiss mercenaries could destroy enemy conscript or volunteer armies more than five times their own size, through superior tactics, technology, firepower, and through sheer bravado. European leaders began to rely on mercenary armies because they appreciated the devastating power that professional soldiers could project. In fact, they began raising their own professional armies. German mercenaries eventually defeated the Swiss, through the use of firearms, and would dominate the merc scene into the 1700s. The idea of German invincibility would last until…

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon burst a lot of bubbles when he came on the scene in 1795. Granted, many pre-existing notions had already been shattered by Revolutionary France’s shocking ideas of warfare. 17th and 18th century to that point warfare had been characterized by small, professional armies. These armies trained hard, fought hard, and were almost universally despised by the people they protected. Standing armies were incredibly expensive and were often viewed as tools of the state. Which they essentially were.

He gets extra style points for the hair.

However, in the 200 years of war between 1580–1780, professional soldiers had almost always been the victors when they went up against militias or levees. This was why almost every single nation-state had developed a moderate to large standing army by 1780. Frederick the Great of Prussia had taken professional soldiering to a whole new level by implementing the general staff system, standard artillery calibers, and professional military education. The small yet mighty Prussian army had smashed the larger French armies over and over during the Seven Years War (1754–1763), leading to an aura of invincibility.

Inspired by American ideals of liberty, equality, and exuberant capitalism, the French people overthrew their government and declared themselves a democracy.

Enter the French Revolution. Inspired by American ideals of liberty, equality, and exuberant capitalism, the French people overthrew their government and declared themselves a democracy. French leaders also noticed how volunteer soldiers in the American Army had managed to stave off the professionals from Britain and Hess (German mercs). They took the idea one step further and created mass conscription, with a twist: a cause to fight for. The French Revolutionary armies won battle after battle against their neighbors, through the use of sheer manpower. Massive 300,000 man French armies would literally overpower the largest army that Austria or Spain could produce, which caused a crisis of faith for other European countries: they could continue to use very expensive professionals (and incur the time and cost it took to replace losses) or they could expose their people to democratic ideals and enlist them into their ranks.

Europe was already reeling from this idea when Napoleon showed up in Italy in 1797 and proceeded to destroy the Austrian armies in detail. His tactics and techniques would be studied and emulated for the next eighteen years, as war became the profession of Europe. He took conscript armies, trained them, instilled pride in them, and then turned them loose against the professionals of Europe (i.e., Prussia) and blew them away. Such was his impact on the profession of arms that he is still studied to this day. Even in…

The U.S. Army

Remember that bit about professional armies being unpopular? Yeah, the new United States hated the thought of a standing army so much that the U.S. Army after the American Revolution consisted of a few hundred troops at West Point and another thousand in the Ohio Country. It was far from a professional organization. America decried the large, professional armies of Europe, blaming them for the constant wars and bankruptcy there. Instead, we would rely on the militia. The idea was that militia units would be called into Federal service if an enemy threatened, negating the need for a large regular Army. The first trial for the militia was the War of 1812. They failed epicly. Apparently, just giving a man a gun and pointing him towards the enemy does not make him a soldier. Also, militia proved reluctant to invade Canada repeatedly, a favorite tactic of the early War Department.

Sir, do we really go rolling along, or is that just a metaphor for the transience of life?” “Shut up and fetch my damn horse.

America decried the large, professional armies of Europe, blaming them for the constant wars and bankruptcy there.

While the aura of the staunch, untrained militiaman remained after the war, the War Department recognized that in order for the volunteer force to actually work, they would need training prior to going to war. Rather than call up the militia, the President would issue a call for volunteers. These volunteers would undergo several months of training before going off to war. Training became standardized through the use of drill manuals (doctrine) and professional officers, many of them West Point graduates (most of whom left the service after four years to go get rich working for the railroads), were put in the volunteer ranks. This practice began in the Mexican-American War and continued through the Civil War and Spanish-American War. It was incredibly successful. The regular Army remained small, never marshaling more than 30,000 men in the ranks until after 1900. Indeed, the idea of a large regular Army was still novel after World War II.

World War II brought about a change to American thought on large armies, as we adapted to our new place in world politics. A large regular force was required to counter the growing Soviet Union. Whereas the Army had before relied on National Guard divisions to serve as the basis for large-scale mobilizations, they now moved the Guard to an operational reserve to back-fill or augment active duty units. With this change came a growing need for better military education and doctrine.

Most soldiers cannot say that their sole occupation for their entire lives is the administration of violence.

So. The burning question: is the current U.S. Army a profession? From a historical standpoint, I am going to have to say that we are not. Yes, there are some few that stay in twenty to thirty years and make a career out of it. But for the vast majority of soldiers, the Army is a place that they pass through on their way to the rest of their civilian lives. Most soldiers cannot say that their sole occupation for their entire lives is the administration of violence. The one exception I would make is the Special Operations Forces community, where they embrace a lifestyle that is embued with the administration of violence and its members tend to serve for longer periods.

As we confront the future of the Army’s force structure modeling, we need to ensure that we don’t lose sight of the professional over the bureaucratic.

However, I do believe that as a whole, the Army inculcates the important aspects of a profession: values, traditions, training, and culture. These traits often make those who pass through the Army better people and more apt to succeed in their civilian lives. On the other hand, the Army has also developed a bureaucracy, which oftentimes overburdens the professional aspect of Army life with administrative humdrum and special projects. As we confront the future of the Army’s force structure modeling, we need to ensure that we don’t lose sight of the professional over the bureaucratic.

Angry Staff Officer is a first lieutenant in the Army National Guard. He commissioned as an engineer officer after spending time as an enlisted infantryman. He has done one tour in Afghanistan as part of U.S. and Coalition retrograde operations. With a BA and an MA in history, he currently serves as a full-time Army Historian. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

The American Way of War: And Why it Brings so Much Baggage

It is said that Germans after World War II stated that they did not like to fight the Americans, as they never stuck to their own doctrine or tactics. Russian doctrine too stated that U.S. forces were unpredictable because all their plans went to hell once a battle had begun. Perhaps that is why one of the great U.S. Army maxims is “No plan survives first contact.” It is true that we tend to bring some “innovations” to war, intentional or not. This could be termed the “tactical” American Way of War. Scholars have spent a lot of time, ink, and breath arguing what the “American Way of War” is, or even if one exists. Russel Weigley has argued that the American Way of War is to bring overwhelming force to bear on the enemy and crush them in absolute and total victory. For myself, hardly daring to even call myself a scholar, I will leave that argument to others with more money and time, but I do have a theory on what I like to call the “American Penchant of War.”