Robert M. Farley and Davida H. Isaacs’s contribution to both fields of international relations and intellectual property lies in their ability to explain the legal system that results in the diffusion of military technology in some cases. The diffusion of military technology is explained in the book by the difference in political factors, organizational structures, or protective security frameworks. The legal explanation for the commonality of some military technologies is not well understood but is a significant factor for explaining why some military technologies are more accessible and widespread than others. Further, their work is of contemporary importance noting the monolithic nature of the global defense industry, consisting of public and private partnerships as well as collaborative approaches to high end military technologies that require complex legal frameworks.

The Battle of Bataan and the Bataan Death March

The Battle of Bataan and the Bataan Death March are some of the more grueling stories from the Pacific War. While justice after war remains a contentious issue, it is important to note that remembrance is central to nation-building and recovery, and instilling a sense of pride in those who served and sacrificed during this part of the Pacific War.

#Leadership and the Art of Restraint

Major General Cantwell’s words articulate the frustration of having to justify actions at the tactical level to those far removed from the area of operations. There are certainly important reasons for having to do this, such as the need to update higher levels of command with the progress of operations, and to explain why certain incidents have occurred. Indeed, accountability for decisions made and actions taken is an enduring feature of civil-military relations in democratic nations.

The #FutureOfWar and the Fight for the Strategic Narrative

Stories or narratives are an important construct that unite and sustain human communities. These narratives are a fire around which individuals, nations, and peoples gather. Based on them we celebrate a common history, language, or culture and they have the power to inspire a sense of meaning for life — they provide hope for the future.

Stories provide ideas which Kennedy referred to as “endurance without death.” For as long as narratives form the fabric of human existence, and for as long as war remains a human endeavor, the fight for the strategic narrative during times of conflict becomes imperative. Consequently, any discussion of the future of war must include consideration of how the battleground for ideas can be won through a persuasive story that can inspire action in people and government and thus the military.

‘A man may die, nations may rise and fall, but an idea lives on. Ideas have endurance without death’.

John F. Kennedy

Strategic narratives also help develop the rationale for war efforts. Without them nothing rallies or binds people to a common cause. More importantly, without a strategic narrative, there is no story that provides an alternative voice to those whom we fight. This is evident in the fight against extremist organisations such as ISIL, who has developed a glossy and sensational communications product that creates emotional connections with people and has proven to be a highly effective recruitment tool.

The Importance of the Narrative to Human Existence

When I think of the word “narrative,” I immediately think of those various human civilizations that have passed on their language and culture through storytelling. Australian Aborigines make reference to “The Dreaming” or “Dreamtime,” which has various meanings within different Aboriginal groups. However, it can be summarized as “a complex network of knowledge, faith and practices that derive from stories of creation, and it dominates all spiritual and physical aspects of Aboriginal life.”[1] This network of knowledge has been passed on over thousands of years through generations sharing stories. Or simply through oral histories.

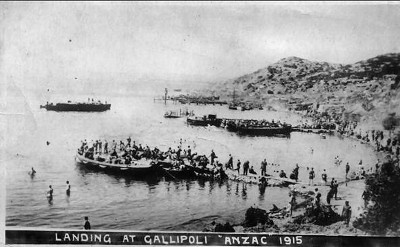

According to one Marine Corps officer, LtCol John M. Sullivan, in an article called ‘Why Gallipoli Matters: Interpreting Different Lessons from History’, “[t]he very word ‘Gallipoli’ conjures up visions of amphibious assault and failure of what might have been.” Gallipoli was indeed a military failure, but that aspect of its narrative has become subsumed by a stronger story about the birth of the Australian nation, an idea that was borne out of the work of Australia’s official war correspondent, C.E.W Bean. This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Gallipoli landings and hence the spiritual birth of Australia, and the dominant narrative will take on an irresistible force with celebrations across the country, which will be spread over the next four years [2]. The facts of the military campaign occupy only a marginal part of the celebrations, reserved only for the military historians or those with a passing curiosity. The details surrounding the events of the 25th April 1915 have been overborne by a greater need for a nation to express its sense of national identity. This highlights that the dry facts are sometimes not as important as the story and the emotions that the narrative conjures in those who engage with it [3].

I wanted to share these examples to highlight the primal nature of stories and their link to human emotion rather than rational human cognition. According to Cody C. Deistraty in ‘The Psychological Comforts of Storytelling’:

‘[s]tories can be a way for humans to feel that we have control over the world. They allow people to see patterns where there is chaos, meaning where there is randomness. Humans are inclined to see narratives where there are none because it can afford meaning to our lives a form existential problem solving.’

Stories also enable an understanding of others and drawing connections with seemingly distant issues.

The Importance of the Strategic Narrative to the Future of War

The importance of narrative, how it powers human emotion, and its relationship to war becomes evident when considered through the frame of Clausewitz’ theory about human emotion within the construct of the ‘paradoxical trinity.’ He said:

“War is more than a true chameleon that slightly adapts its characteristics to the given case. As a total phenomenon its dominant tendencies always make war a paradoxical trinity — composed of primordial violence, hatred, and enmity, which is to be regarded as a blind natural force; of the play of chance and probability within which the creative spirit is free to roam; and of its element of subordination, as an instrument of policy, which makes it subject to reason alone.

The first of these three aspects mainly concerns the people; the second the commander and his army; the third the government. The passions that are to be kindled in war must already be inherent in the people; the scope which the play of courage and talent will enjoy in the realm of probability and chance depends on the particular character of the commander and the army; but the political aims are the business of government alone.

These three tendencies are like three different codes of law, deep-rooted in their subject and yet variable in their relationship to one another. A theory that ignores any one of them or seeks to fix an arbitrary relationship between them would conflict with reality to such an extent that for this reason alone it would be totally useless” (emphasis added) [4].

In his book, The Direction of War, Sir Hew Strachan considers that strategy formation in the 21st century neglects the people, which is a significant oversight because “[t]he people are the audience for war” and they must be factored into strategy formulation and operational planning. Strategic narrative is vital in engaging the people — in persuading the adversary’s potential recruits/supporters to either stay out of the fight or to support our efforts; as well as convincing our own populations to support our military endeavors in pursuit of key national interests [5]. For this reason, a strategic narrative is a means to ensuring that the people, military and government “become three in one in reality as well as in Clausewitzian theory” [6].

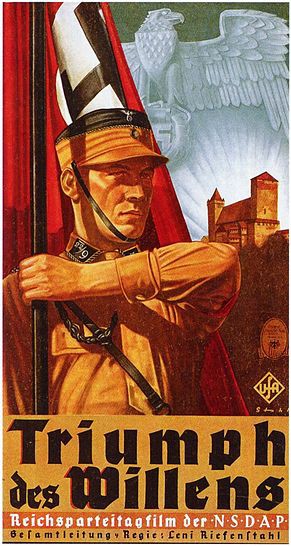

The battle between competing narratives is not new. A battle for ideologies underscored the Second World War. Hitler’s anti-Semitic rhetoric and territorial ambitions were delivered with the pomp and ceremony of rallies and associated symbology. Nazi propaganda films, such asTriumph of Will were aimed at stirring emotion and hitting the German population in the collective ‘feels.’

…they used emotion to convey a message and obtain understanding, rather than dry statistical and bureaucratic language to convince the respective populations of the need to go to war.

On the Allied side of the fight was the seven-part film Why We Fight, which was aimed at emphasising to US servicemen the reasons for US involvement in the war against Germany and Japan, and to unite the nation behind a common cause [7]. These films were effective in that they used emotion to convey a message and obtain understanding, rather than dry statistical and bureaucratic language to convince the respective populations of the need to go to war.

Arguably, it is easier to have a strategic narrative in a total war where there is a clear existential threat to a nation. Limited wars conducted on distant shores are a relatively more difficult to “sell.” For this reason, a strategic narrative is vital in a limited war because there is an ongoing need to keep the people appraised of how the war is unfolding and to maintain their support for the often protracted conflicts that we have so far experienced in the first decade of the 21st century.

A strategic narrative also plays a vital role in providing a protective function (or ‘counter-narrative’) against the story conveyed by the adversary. The large numbers of citizens from many nations, including Australia and the US, going to Syria and Iraq to fight alongside ISIS provides an ongoing reminder of the need to have a ‘counter-narrative’. The difficulties in countering ISIS in this regard is covered off by Simon Cottee’s article in The Atlantic posted here.

A few considerations for how to build an effective strategic narrative, particularly in a counter-insurgency setting, have been discussed by Col. Stephen Liszewski USMC here. Jason Logue, in a previous post on The Bridgealso provided a detailed discussion on how to constructively engage in the fight for the dominant and more persuasive story through the use of appropriate language and having a nested approach to strategic communications.

Preparing Future Leaders

The preparation of future leaders for future warfare that will inevitably involve the fight for the dominant narrative is difficult and will require breaking existing cultural norms. This can be achieved through including the strategic narrative in professional military education; and reacquainting ourselves with strategy formulation.

Professional military education and strategic narratives. When someone mentions the strategic environment, the instant reaction is to start thinking about things like regional military spending, socio-economic and environmental pressures that can widen fissures in the security setting, and pre-existing tensions between countries based on history, etc. However, there is little discussion about the “information environment,” as a subset of the “strategic environment,” wherein competing narratives reside.

This is particularly important when it comes to ‘whole of government’ efforts that direct many elements of national power to a common cause. The fight against ISIL is an example where various elements of national power are engaged, and where a unifying strategic narrative that offers an alternative is imperative. Preparing future leaders to engage in this fight for the dominant narrative is challenging as it requires a change in culture and a broadening of the collective perspective. Perhaps a relatively useful starting point is in professional military education — through war colleges and staff colleges as part of studying strategy; and using a historical study of strategic narratives in past conflicts using Sir Michael Howard’s approach of studying depth, breadth and context.

Reacquainting Ourselves with Strategy

Before an effective and unified strategic narrative can be constructed and deployed as a credible and viable alternative to that offered by the adversary, there is a need to have a strategy that forms the foundation of the narrative. In the fight against ISIL, this seems to be missing. Much of the political oratory regarding actions to be taken against ISIL revolves around mission verbs: “degrade” and “deny” [8]. Arguably, this is not a strategy as it fails to link how military force is to be used to achieve political objectives and is merely declaratory of actions that should be expected in war (i.e., to degrade or deny the enemy). Sir Hew Strachan, in The Direction of War, examined a number of recent conflicts and strongly criticizes national leaders in the United States and Britain for entering into conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan without a clear strategy.

…it is clear that strategic acquaintance must begin with senior military leadership, who are expected to provide advice on the use of military force to civilian leaders…

Sir Hew discusses the impact of the Cold War in diminishing the capacity for strategic thought and strategic formulation caused by the conflation of strategy with policy due to the specific existential threat that nuclear war posed [9]. Ensuring that future leaders reacquaint themselves with strategy and its formulation is a significant challenge due largely to the need for a cultural shift. It is not for me to detail how this is to be done, but it is clear that strategic acquaintance must begin with senior military leadership, who are expected to provide advice on the use of military force to civilian leaders in nations where civil control of the military is a fundamental tenet of liberal democracy. It will require a serious, objective consideration of recent conflicts and an examination of where we were found wanting in terms of strategy. This may require the help of experts in strategy (such as Sir Hew) to guide military leaders on this path to strategic re-acquaintance.

The current fight for the strategic narrative is not in our favour; as shown by the multitude of willing volunteers answering ISIL’s call. While a topic such as the future of war evokes mental images of technologically advanced platforms, cyber capabilities, and omniscient battlespace awareness, we cannot forget about the enduring human aspect of war. While war remains a human endeavor, and stories/narratives are a way for humans to use emotion to understand complex phenomenon, the battle for the strategic narrative remains vital. If we fail to engage in this fight, the future of war will look very much like the recent past where we win the tactical engagements but lose the war.

Jo Brick is an Australian military officer who has served in Iraq and Afghanistan, an Associate Member of the Military Writers Guild, and is currently writing a thesis on Australian civil-military relations. The opinions expressed are hers alone and do not reflect those of the Australian Defence Force.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] See Australian Museum: http://australianmuseum.net.au/indigenous-australia-spirituality

[2] For a sense of the scale of ‘Gallipoli: 100 Years On’ celebrations, seehttp://www.anzaccentenary.gov.au/

[3] See Dr Peter Stanley, ‘Why does Gallipoli mean so much?’ ABC News Online, 25 Apr 08: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2008-04-25/why-does-gallipoli-mean-so-much/2416166 (accessed 03 March 2015).

[4] Carl von Clausewitz, On War. Translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, (Princeton: Princeton University Press) 1984, 89.

[5] Hew Strachan, The Direction of War (New York: Cambridge University Press) 2013, 278–281.

[6] Strachan, 281.

[7] Charles Silver, ‘Why We Fight: Frank Capra’s WWII Propaganda Films, MOMA http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2011/06/07/why-we-fight-frank-capras-wwii-propaganda-films/ (accessed 03 March 2015).

[8] See Obama speech:http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2014/09/10/president-obama-we-will-degrade-and-ultimately-destroy-isil (accesed 04 March 2015).

[9] Strachan, 16.

Mea Culpa or "The law is easy"*

*Conditions Apply

Will Beasley provided a different perspective on the #Professionalism debate in his piece on The Rise and Fall of US Naval #Professionalism. What I found most interesting was his discussion of ‘The Golden Age of Professionalization’ and Wilensky’s five-steps involved in an occupational group attaining the status of ‘profession.’ Beasley’s article was intended to provide a response and another perspective on my previous post ‘The Military #Profession — Lawyers, Ethics and the Profession of Arms’.

I noticed that exception was taken to my comment: ‘The law is easy — ethics is hard.’ I thought I’d clarify my comment to remove any misunderstanding. My comment was meant to be read in its entirety and to convey the point that, at times, the answer to the legal problem is easier when compared to the ethical quandries that accompany it. As Winston Churchill once remarked, and I paraphrase, foreign policy choices (which include decisions about how international law is applied) are often between the dreadful and the truly awful. This is the context I had in mind when I made my comment.

…at times, the answer to the legal problem is easier when compared to the ethical quandries that accompany it.

‘The law is easy-ethics is hard’ refers specifically to the application of the laws relating to the use of force (jus ad bellum), the laws of war (jus in bellum); and national policy in operational contexts. In many respects, the application of the laws of war are guided by national policy, and as a result the ‘answer’ to a particular legal question is given to us by the national command authority or coalition headquarters through rules of engagement or other operational orders that impact on how an operation is to be conducted. The difficulty is where the law or the policy is clear but its application may create a complex ethical dilemma. This is why the law is *relatively* easy and ethics is comparatively harder.

One example that comes to mind is the situation during the Bosnian conflict, involving the Dutch Battalion — Dutchbat — who were ostensibly guarding the enclave of Srebrenica, a United Nations ‘Safe Area’. The Dutchbat was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Thom Karremans, who decided to act in accordance within the UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR) mandate and orders from UNHQ. The Dutchbat was in an invidious position of having to morally protect the enclave while lacking the military capability to do so. The chain of events leading to the fall of Srebrenica and ethical dilemmas are discussed in more detail elsewhere [1]. In summary, Karremans made the decision to act in accordance with his legal obligation (comply with superior orders and policy) but resulting in the ethical dilemma of being unable to protect those in the enclave from being rounded up and, as the world later learned, falling victim to genocide. In this case, the law was easy — a clear legal answer was available, but was unhelpful in resolving the complex ethical dilemma that unfolded before Dutchbat and Karremans [3].

I extend my apology for any misunderstanding. I don’t mean to offend my learned friends out there. In a domestic context, the law is definitely hard. But in the international system, which is largely one of nations regulating themselves, law is more about politics than jurisprudence [2] and can sometimes be ‘easier’ when juxtaposed against the ethical dilemmas created in the wake of their application.

The Proprietor of ‘Carl’s Cantina’ is an Australian military officer who has served in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Proprietor is an Associate Member of the Military Writers Guild and is currently writing a thesis on Australian civil-military relations. The opinions expressed are hers alone and do not reflect those of the Australian Defence Force.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] See paper by LTCOL P.J. deVin, ‘Srebrenica, the impossible choices of a commander’.

[2] The law as a continuation of politics by other means is a whole topic on its own and frequently discussed over at the Lawfare blog.

[3] If you want to follow the subsequent legal action against the State of the Netherlands brought by Mothers of Srebrenica, a good starting point is here.

#Profession and 'New Model Army'

In an attempt to procrastinate from writing my thesis, I recently read Adam Roberts’ New Model Army. It is a sci-fi story centred on the narrative of an unnamed protagonist who deserted from the British Army but is now a member of a ‘New Model Army’ (NMA) called ‘Pantegral.’ The Pantegral NMA is an amorphous group organised around democratic ideals (for example, its members vote for courses of tactical action during a battle) and use a wiki for communication and coordination. In a sense it is a ‘crowd sourced’ army based on the equality of its members; all of whom have a vote about how the NMA is run and how battles are fought. The story is set in a dystopian future where secessionist Scotland is at war with the rest of Britain and hires the NMA as its armed force. Here’s an extract from the book that gives a flavour for what NMA is all about:

Lets say our eight thousand men, coordinating themselves via their wikis, voting on a dozen on-the-hoof strategic propositions, utliizing their collective cleverness and experience (instead of suppressing it under the lid of feudal command) — that our eight thousand, because they had drawn on all eight thousand as a tactical resource as well as a fighting force — had thoroughly defeated an army three times our size. Let’s say they had a dozen armoured- and tank-cars; and air support; and bigger guns, and better and more weapons. But let’s say that they were all trained only to do what they were told, and their whole system depending upon the military feudalism of a traditional army, made them markedly less flexible; and that each soldier could only do one thing where we could do many things. Anyway, we beat them.

The underlying assumption in the novel was that the NMA consisted of anyone that wanted to fight and that the wiki was practically a ‘deus ex machina’ that suddenly made the amorphous mass an ‘army’ that had the skills and knowledge to take it to the British and win. On the other hand, the British Army was considered ‘feudal’ and inflexible by comparison; and that these very characteristics were what made it less effective on the battlefield than the NMA.

The book painted an interesting backdrop against which all the articles within the #Profession series can be examined, and enables the extrapolation of the fundamental prerequisites to becoming a ‘profession’. There were three key themes about professionalism that leaped out at me while I was reading the book:

- ‘Fighter’ versus ‘Professional.’

- Professionalism and accountability.

- Pendulum of professionalism.

‘Fighter’ versus ‘Professional’

Mike Denny’s article discusses the issue of when a ‘fighter’ becomes a ‘professional.’ He argues that a soldier’s ability to make autonomous decisions, based on extensive knowledge and experience, is what separates the ‘mere fighter’ from the ‘professional.’ A fighter requires some validation or direction from others to proceed with a course of action, while the professional has the confidence to make a decision on their own that is relevant to their assessment of the situation. Based on this assessment, the NMA does not have any professionals because decisions are made by the ‘hive mind’ in the context where quantity (number of votes) trumps quality of decision. The NMA soldier cannot act alone, despite being able to ‘do many things.’

Dedication to learning the art (and craft?) of war is imperative.

Our Pantegral protagonist also criticises the British Army for being feudal and inflexible. However this ignores the concept of ‘mission command’ that is central to the command and control paradigm of many modern military forces. Originally conceived as an enabler for seizing the intiative versus set piece battles, ‘mission command’ (auftrakstaktik for the purists) relies on professionalism and trust — junior leaders must understand commander’s intent and have the expertise and experience to know when to seize the initiative rather than wait to receive an order to take action[1]. Sometimes, as Denny argued, it might just require breaking some rules! As many of the authors in the #Profession Series pointed out, merely joining the military does not make one a ‘professional;’ in the same way that being able to fix some dodgy plumbing based only on YouTube DIY videos does not entitle you to call yourself a ‘plumber.’ Dedication to learning the art (and craft?) of war is imperative. I doubt that such an ethos exists within a Wikipedia/Google-powered NMA.

In order to have accountability, there must be an identifiable entity that has made a decision and, if necessary, against whom some remedial or punitive action can be taken…

Professionalism and Accountability

Many contributors to the #Professional discussion also highlighted the ethical aspects of professionalism. Dr. Rebecca Johnson discussed the obligation to serve someone other than the people who purport to be part of the profession (no self-licking ice cream cones here) and the need to maintain the trust of ‘the people;’ which implies some measure of accountability to ‘the people.’ In order to have accountability, there must be an identifiable entity that has made a decision and, if necessary, against whom some remedial or punitive action can be taken in relation to the decision made.

The NMA narrator derides the ‘feudal’ nature of the British forces. This attitude seems founded on the hierarchical, rank based and seemingly inflexible command and control structure in conventional military forces. This is subsequently compared with the flat organisational structure of the NMA, where all members are regarded as ‘equals.’ This may be good for fostering a sense of belonging and unity, but does little to enhance professionalism. The flat organisational model of the NMA, coupled with the ‘everyone is equal’ culture results in the diffusion of responsibility for the course of action selected. When the primary criteria for a decision is majority rule, holding the decision-makers to account becomes difficult.

As my drill sergeant was fond of reminding my course during our initial training course, ‘you may be defending democracy, but this [the military] is not a bloody democracy!’ The reason is clear — professional organisations require a hierarchical structure through which values and standards are enforced; ‘the knowledge’ passed on; and direction given. Accountability for decisions is relatively clear in the profession of arms — the commander may bask in the glory; but must also bear the burden of any criticism.

Pendulum of Professionalism

Various arguments were made throughout the #Profession series about the relative nature of professionalism. Roster#299 argued that ‘[t]he military is a profession that adjusts its level of professionalism according to how much it is being used;’ with military forces generally being more like a profession in times of relative peace and less like a profession in times of war. This is consistent with the view proposed by Dr. Don Snider (via Nathan Finney) that professions can ‘die;’ and that merely ‘[w]earing a uniform or getting paid to perform a role does not make someone a professional.’ Angry Staff Officer goes further by saying that ‘just giving a man a gun and pointing him towards the enemy does not make him a soldier’. Based on these criteria, members of the NMA are not professionals — they wear a uniform, get paid, and fight some battles. You might as well hire some Halo cosplayers [2]! You won’t get much warfighting professionalism for your buck.

An individual is inducted into a profession after an assessment of skills and knowledge that are central to the profession (call it basic training). This is just the beginning of a long professional journey along a road that never ends — unless you chose to stop (ie retire or are dismissed). The professional may ‘die’ along the way if they do not make the effort to invest in maintaining and improving the skills and knowledge fundamental to the profession of arms. Dr Simon Anglim emphasises the importance of continuing education in maintaining standards within a profession.

…small bands of fighters have, at times, overcome larger and better equipped forces.

Going back to the scenario at the start of this post, our Pantegral protagonist emphasised that a small NMA force defeated a much larger (three times bigger), and better equipped element of the British Army. This scenario is reminiscent of some real world experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan — small bands of fighters have, at times, overcome larger and better equipped forces. Any attempt to identify one causal factor leading to the defeat of the larger force is difficult, but I might humbly posit a possible consideration: the larger, better equipped force is in professional decline. Perhaps the force is no longer dedicated to understanding and studying warfare (its width, depth and context: Michael Howard).

Perhaps the key to avoiding such defeat in the future is to invest in those leaders who have dedicated themselves to understanding the profession of arms (strategy / military history), and who are unrelenting in their pursuit of self-improvement. These individuals will be the touchstones for maintaining the professionalism of military forces, as they lead soldiers/sailors/airmen who many not be as dedicated to the profession, into an unforgiving and binary environment characterised by life or death; victory or defeat.

The Proprietor of ‘Carl’s Cantina’ is an Australian military officer who has served in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Proprietor is an Associate Member of the Military Writers Guild and is currently writing a thesis on Australian civil-military relations. The opinions expressed are hers alone and do not reflect those of the Australian Defence Force.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] I thought I’d throw in the German term for the purist strategist, just as I’d throw in a Latin term for the purist lawyers! For a discussion on auftragstaktikand its modern utility, see John T. Nelsen II, ‘Auftragstaktik: A Case for Decentralised Battle’ Parameters, September 1987.

[2] As the proud owner of a partially constructed (and therefore not yet vetted by the 501st Legion) Stormtrooper outfit, I just want to make it clear that I have nothing against cosplayers!

The Military #Profession: Lawyers, Ethics, and the Profession of Arms

The military is a profession. It shares the characteristics that are commonly attributed to professional fields such as the law or medicine. As a lawyer and military officer, I am often reminded that I am the member of two professions and must uphold and observe the distinct codes applicable to each.