When discussing the struggles of the U.S. military in the early years of the Iraq War, Davidson uses the phrase “adapting without winning,” a formulation that surely continues to accurately describe the American experience of the post-9/11 wars. Despite the optimistic characterizations on the dust jacket that frame this book as a manual for how to succeed at counterinsurgency, though, Lifting the Fog of Peace sounds a note of caution about the gap between tactical adaptation and strategic success, even as it lauds the U.S. military for the evolution of its lesson-learning apparatus.

Cosmic Thinking: A Ptolemaic View of Military Decisions

Operational and strategic level leaders cannot get caught in the rapid pace of tactics, but neither can they ignore the fact that decisions at the tactical level must proceed at the pace demanded by the situation. When operational and strategic leaders increase the pace of decision-making, it can lead to a chasing of the bright and shiny object mentality. Decisions in these orbits include a set of dialogues and tend to be iterative. Further, leaders at all levels must consider the complexity of decision making at each level above and below them.

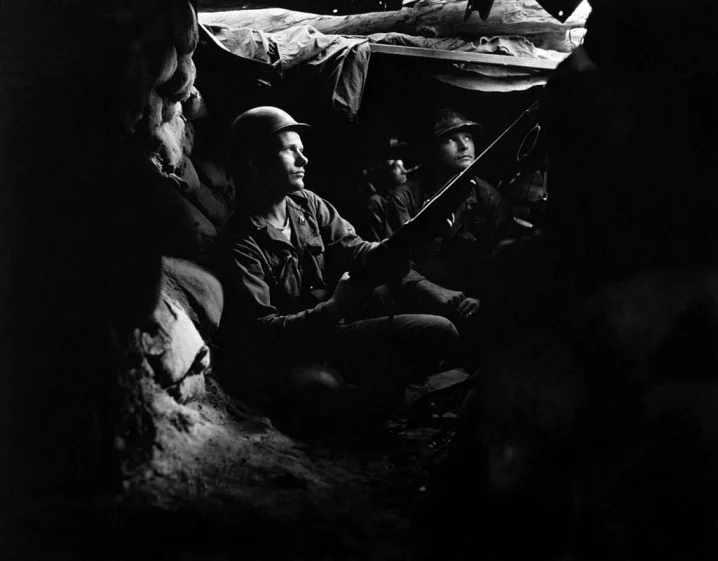

War Isn't Precise or Predictable — It's Barbaric, Chaotic, and Ugly

Democracy will always benefit from the requirement to persuade the public––to gain consensus on, and legitimacy for, the use of force in order to defend or pursue national interests. If this opportunity is ceded for fear of being unconvincing, or in fear of explaining the ugliness it will entail, then a society will find itself bereft of clarity in the political objective and therefore unable to craft strategy appropriate to the task at hand. Furthermore, the failure to have these discussions leaves the populace underprepared for the brutality and sacrifice that war may require.

The Wages of War Without Strategy

In this––our final installment––we appeal to each element of the Clausewitzian Trinity to do its part. To remain silent as practitioners of policy and war, we believe, would perpetuate the betrayal of those troops and civilians––American and foreign––who have made the ultimate sacrifice for reasons this country still struggles to articulate.

The Wages of War Without Strategy

War and violence decoupled from strategy and policy—or worse yet, mistaken for strategy and policy—have contributed to perpetual war, or what has seemed like 15 years of “Groundhog War.” In its wars since 11 September 2001, the United States has arguably cultivated the best-equipped, most capable, and fully seasoned combat forces in remembered history. They attack, kill, capture, and win battles with great nimbleness and strength. But absent strategy, these victories are fleeting. Divorced from political objectives, successful tactics are without meaning.

Thoughts on the Practicalities of Implementing the Iraqi National Security Strategy

Is it possible to intervene in another nation-state and pushback against the weight of that nation-state’s history? Can the weight of history be sufficiently balanced by intervention, allowing for the creation of enduring conditions that protect the outsider’s strategic interests? Today, the experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the constraints on resources and time, probably make this an unattractive policy option. Instead, managing not resolving, the threats that pose risk to strategic interests is probably a more reasonable policy approach. This means accepting that an intervention in the affairs of another nation-state is limited to advise, assist and enable; and that the intervention will be a long-term commitment that works with the grain of history to achieve incremental progress.

The Generals in Their Labyrinth: #Reviewing High Command

The fact that our most cherished ally is no longer able to analyze its own strategic situation, or participate fully in our strategic debates, should be distressing. Britain’s generals, brilliant as they may be, are trapped in a series of historical and organizational labyrinths. Needless to say, this situation may change, and Elliott is one of many voices calling out for reform. Until then, America must remain wary of allies who promise more than they can deliver.

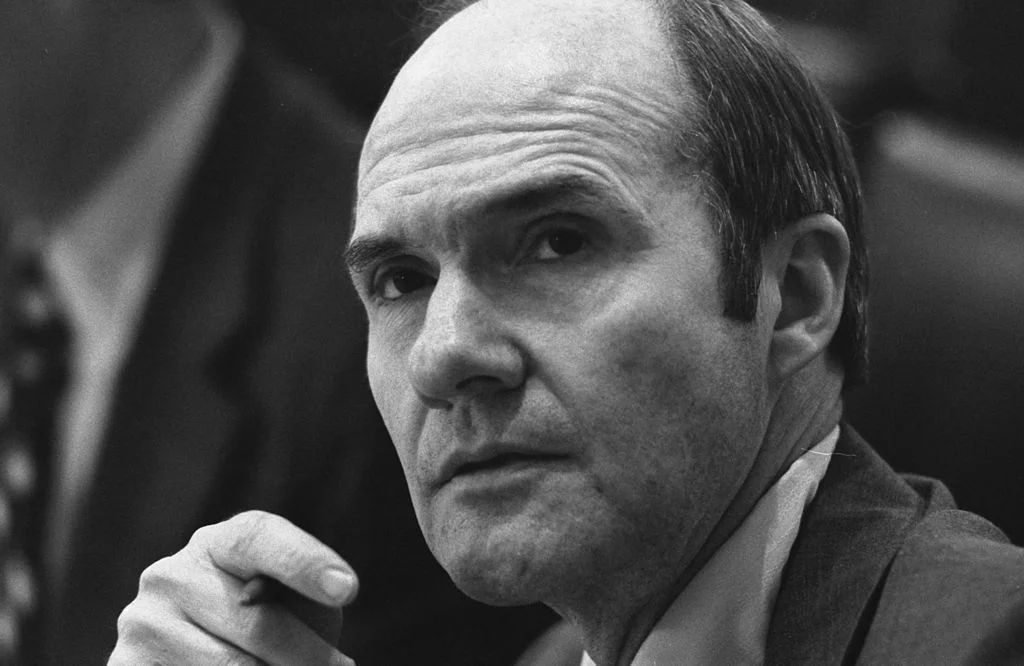

#Reviewing Consequence: A Memoir

Jolting the System: Organizational Psychology and the Iraq Surge

Regardless of the criticism of Petraeus’ impact on the surge and the Army’s culture, the lessons of his actions as a change leader before and during the surge in Iraq serve as archetype for military leaders to study...Change leadership requires clear vision setting, adroit communication skills, generating energy, achieving organizational alignment, and other requisite leader competencies. This skill set applies at both the strategic general officer level and the tactical platoon leader level.

2026: Operation Iranian Freedom

We all knew this would happen. When the U.S. and Iran signed the nuclear deal in 2015, some thought it was just delaying the inevitable. I remember one of my professors at MIT comparing the deal to the Peace of Nicias during the Peloponnesian Wars. I guess he was right, just as with Athens and Sparta, the U.S.- Iran nuclear deal was a false peace.

#Reviewing Success and Failure in Limited War

Strategic performance is strongly affected by the state’s information management capabilities. Top policymakers must have the ability to understand the environment in which they are acting (outside information) and how their national security organizations are behaving in that strategic environment (inside information). Strategic risk assessment is based on an understanding of the opponent’s strengths and weaknesses, the challenges and opportunities present in the international environment, and the capability of the state to act in a purposeful way along multiple lines. Without sound outside and inside information, risk assessments will suffer, as will the quality of strategy.

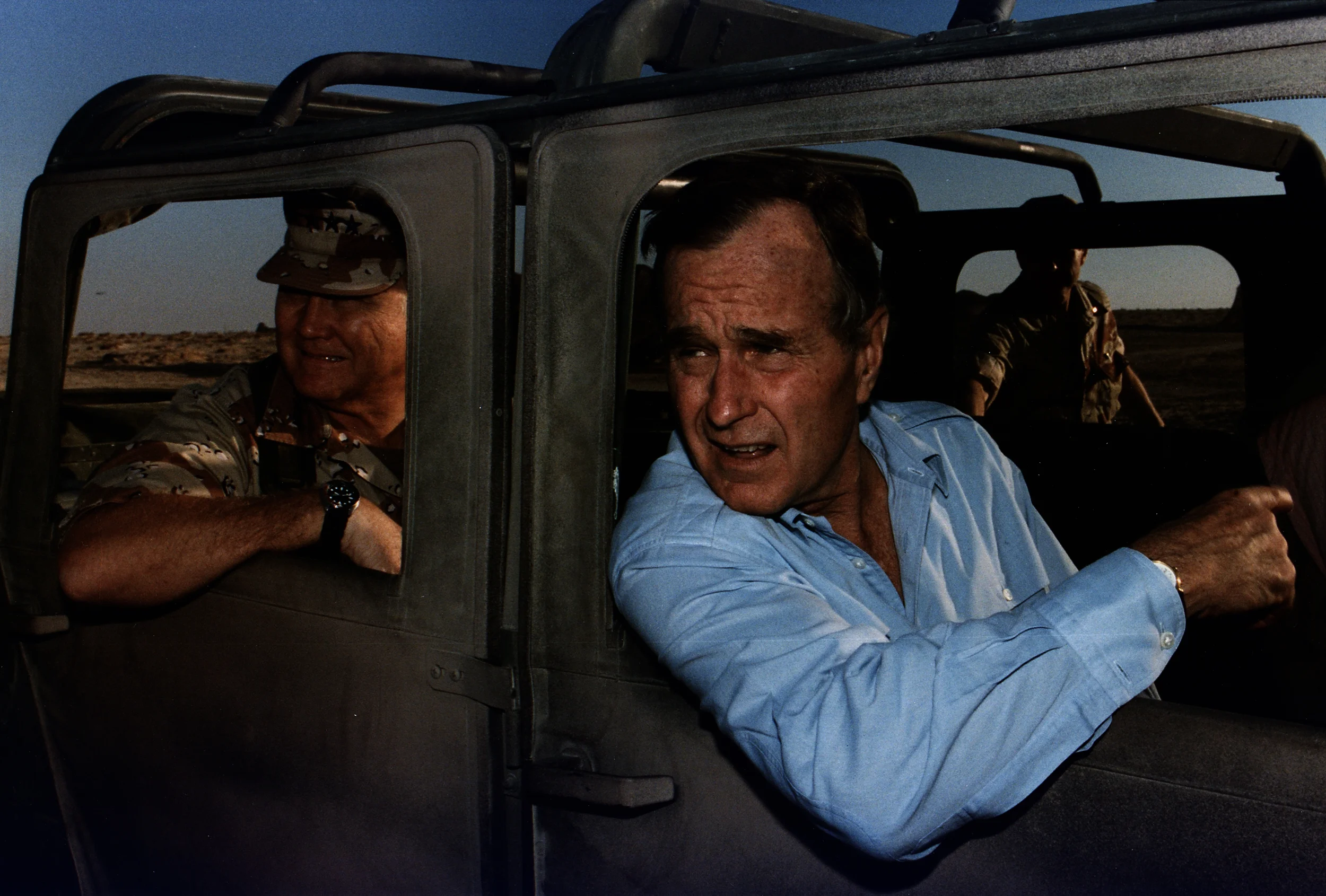

Eagle Troop at the Battle of 73 Easting

The Battle of 73 Easting (a north-south grid line on the map) was one of many fights in Desert Storm. Each of those battles was different. Individual and unit experiences in the same battle often vary widely. The tactics that Army units use to fight future battles will vary considerably from those employed in Desert Storm. Harbingers of future armed conflict such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, ISIS’s establishment of a terrorist proto-state and growing transnational reach, Iran’s pursuit of long range ballistic missiles, Syria’s use of chemical weapons and barrel bombs to commit mass murder against its citizens, the Taliban’s evolving insurgency in Afghanistan and Pakistan, North Korea’s growing nuclear arsenal and that regime’s erratic behavior all indicate that Army forces must be prepared to fight and win against a wide range of enemies, in complex environments, and under a broad range of conditions.

#Reviewing Success and Failure in Limited War

In the Information Institution Approach, Bakich gives critical importance to whether or not key decision makers have access to multi-sourced information and whether the information institutions themselves have the ability to communicate laterally. When information is multi-sourced and there is good coordination across the diplomatic and military lines of effort, Bakich predicts success. When information is stove piped and there is poor coordination, he predicts failure. Where the systems are moderately truncated, Bakich expects various degrees of failure depending on the scope and location within the state’s information institutions.

2026: Operation Iranian Freedom

It was predictable. The moment U.S. policymakers signed a nuclear deal with Iran, it made future military action inevitable. What was Iraq in 1991 if not a foreshadowing of this more deadly situation? United Nations Resolution 687 called for Iraq’s leadership to destroy, remove, or render harmless its chemical and biological weapons as well as all ballistic missiles with a range greater than 150 kilometers. That resolution, at least in part, set the stage for the series of events leading to Operation Iraqi Freedom. This newer deal created its eastern brother, Operation Iranian Freedom.

“Boots on the Ground” is the Wrong Question for Iraq and ISIS

"Instead of posing the ‘boots on the ground’ question and the military focus it embodies, the question should rather be, “How does the U.S. stabilize Iraq and Syria?” This more refined question shifts thought to the wider array of political, cultural, and economic contexts, and to the long-term implications of the various possible solutions to the threat that ISIS presents. By focusing instead on the politically-charged decision of whether to send in troops, the U.S. instead creates a conversation that is emotionally charged—by two, decade-long wars—and hampers future solutions by drawing implicit lines in the sand."

#Reviewing "The Strategist"

Sparrow’s account of Scowcroft is full of insight and surprises. Readers will take pleasure in Sparrow’s depiction of the NSC debates, executive-level relationships, and the nuanced recollections of a consummate strategist. Anyone interested in understanding the unique role of the NSC in foreign policy and executive-level decision-making during the Nixon, Ford, Reagan, or first Bush administrations will be interested Sparrow’s work. This book also has practical use for journalists, political scientists, as well as students of U.S. security strategy, foreign policy, and American government.

Warfare by Spoiler: #Reviewing “Team of Teams”

Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. Stanley McChrystal. Portfolio, 2015.

But this is no winter now.

The frozen misery of centuries breaks, cracks begins to move;

The thunder is the thunder of the floes,

The thaw, the flood, the upstart Spring.[1]

Something’s happening to power. Failure to take this pulse and your combat unit, government, or company starts to flail. Failure to check yourself and your organization, ask the tough questions about whether you are trying to preserve the static known at the expense of the agility you need to survive, and you probably won’t.

The pace of technological change and scale of information instantly available have fostered a world dis-order where chaos and disruption are force multipliers.

Iconoclasts in, old guard out.

Agents of change are no longer obviously the establishment elite, the uniformed combatant, or the most efficient system. Communication is reduced to acronyms and messages are sent in seconds by fleeting identities which are casually discarded. Celebrity requires no talent. Those days belong to the history books. Or rather history apps.

The new order is unafraid of change, constantly looking to replace in place, do more with less. Reaction is the new action. In politics there is a voter appetite for the anti-establishment outsider, throughout the Middle East and parts of Africa the majority population is no longer willing to endure decades-long authoritarian rule. It’s open season on commerce. In the disruptive “sharing economy” of Uber, Air BnB and where individual reviews can make or destroy a chef’s reputation overnight, the individual has never been so connected to so many. And it’s all remote control. Just as easily, he or she disappears. By going off the grid.

Welcome to the age of warfare by spoiler.

In combat too, the individual wields disproportionate power. It’s easy to disrupt, hard to build and sustain. But if the near goal is simply chaos and you have a means of rapid, widespread communication, you do not waste time or resources on painstaking recruitment and training. Just go start a fire and watch it burn. Or walk away. Welcome to the age of warfare by spoiler.

This is the operational environment and enemy General McChrystal and his team at the forward base of Joint Special Operations Command (or the Task Force) faced in Iraq in 2004 where the nascent origins of al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) were gaining a foothold.

But this is not a war story as the introduction makes clear. Instead, the experience of war is the scene and the enemy is the instigation for a most unlikely case of organizational upheaval. What happens when the world’s most elite counterterrorist force finds it cannot keep up with a miscellaneous band of radical fighters? McChrystal and his team want to explain it to you and believe their experience on the cutting edge of counterinsurgency reveals not only what is changed about warfare but the world itself. They discovered a most uncomfortable truth: to succeed they had to get out of their own way.

“We explore the unexpected revelation that our biggest challenges lay not in the enemy, but in the dizzyingly new environment in which we were operating, and within the carefully crafted attributes of our own organization.”[2]

With virtual and literal bookshelves crammed full of organizational transformational advice you could be forgiven for wondering why the experience of US special forces in a war which continues to pose more questions than answers has anything relevant for you or your organization. All the more so, for the daily headlines from a region which continues to hemorrhage from its injury in an evermore complex, compounding fracture.

You might forgive yourself a second time for wondering why the experience of the US military in Iraq holds relevant lessons learnt other than what not to do. That is one reason this book is not a war story but an examination of what happens when an organization faces an existential threat: the best resourced and trained military force on the planet found that wanting the enemy to be the one you trained for does not make it so and failure to get this right means the difference between mission success and failure.

The book is best read as a journey which allows the reader a front seat view of how the mighty were fallen.

While the title Team of Teams seems like a missed opportunity for something more descriptive this should not put you off the book. What its title lacks in imagination the book makes up for with the compelling witness from the frontlines of a complicated war declared on a tactic. The book is best read as a journey which allows the reader a front seat view of how the mighty were fallen. But this is no story of defeat. Rather, it is an insider look at how the Task Force learned from its enemy and adapted in order to defeat it.

Years later, something was missing from this experience, the journey somehow incomplete. General McChrystal now retired and several members of his team from Iraq set out to explore whether the experience of transforming an elite military organization was a one-off experience or if it might have broader application. They believed it did but the experience was organic, it happened in a specific time and place which could not be now replicated. So they set out to re-examine what had happened and build the theoretical underpinning as to why transformative change was possible. The results led to the conclusion and claim for a proven framework for organizational change.

While the book’s most immediate audience is the private sector companies the McChrystal Group aims to court, the underlying message is by no means limited by a single demographic. Initial results prove their assumption correct. In addition to private sector success, “Big Army” has paid attention. In a recent call for papers the Combined Arms Center has issued an invitation for responses on the topic of “Empowering to Win in a Complex World: Mission Command in the 21st Century.” The principles of mission command to be explored bear a remarkable resemblance to the principles McChrystal Group’s methodology for organizational transformation.

Premise — What if you get it?

The premise of Team of Teams is that we live in a dynamic and interdependent world characterized by upheaval and change. The old rules no longer apply and the organizational model that has dominated both military and commerce since the Industrial Revolution is outdated. When faced with a threat, as the Task Force did in Iraq, the traditional response of doubling down on efficiencies and just doing what you know but better is no longer sufficient. Instead, “adaptability, not efficiency, must become our central competency.”[3]

If you accept this premise at the outset and your reason for reading the book is to understand the experience of the Task Force in Iraq, get ready to be patient. Interspersed between vignettes from Iraq are carefully researched sections on the nineteenth century origins of the efficiency model and how it evolved over time. The Iraq narrative is interrupted with examples on leadership from military history, team dynamics in a hospital emergency room and various industries from business to aviation. All of which are interesting and the content valuable but in places reads more like a textbook. The book’s structure reflects its four authors: Three with shared combat experience in Iraq and a fourth researcher.

Survival is Counterintuitive

To defeat an enemy you have to quantify them in order to allocate and prioritize resources. The challenge for the Task Force was that their enemy was literally their structural opposite:

“We were struggling to understand an enemy that had no fixed location, no uniforms, and identities as immaterial and immeasurable as the cyberspace within which they recruited and developed propaganda.”[4]

Despite this shape-shifter construct the narrative gives a face to the enemy in the form of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi who emerged as the leader of Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI). As the Iraq story unfolds, Zarqawi takes on a significance which is understandable given the need to quantify and demonstrate the value of their process of overhauling the Task Force. The narrative builds to the achievement of tracking down and killing Zarqawi which is at once impressive and convenient. The authors acknowledge the limits of this significant activity with humility and the illustration stands as a success.

The hardest part of making a case that the Task Force’s experience in Iraq applies to you and your organization is the unfortunate record of the US-led coalition in Iraq and subsequent events which have led to the world’s largest humanitarian crisis.

Team of Teams understandably steers clear of the decision to invade Iraq and the role of the conventional forces. However, at no point in the fight against AQI was it separate from the US civilian leadership’s decision to alienate the most powerful, connected and well-trained Sunnis with the ban against former Baathist party members participating in the new government. Nor was their fight separate from the conduct of the far larger number of conventional forces that made up the coalition.

It was not just that the Task Force could not keep up with the enemy, it’s that the operational environment favored the tactics of the spoiler.

In AQI the Task Force faced less a hostile military organization, however decentralized, and rather a militant organism. They weren’t just fighting AQI, they were fighting in a vicious circle where the very footprints of coalition forces and reconstruction projects designed to win hearts and minds created endless targets of opportunity. The unexamined logic of the invasion and end-state of defeating the enemy was security. This fed perfectly into the emerging organism that was the counterinsurgency of which AQI was part.

A parasitic organism lives off of another organism (its host). It survives by deriving nutrients at its host’s expense. As the occupation wore on, AQI adopted the habits of a parasitic organism feeding off the very presence of its enemy.

It was not just that the Task Force could not keep up with the enemy, it’s that the operational environment favored the tactics of the spoiler. Put another way, its not just that AQI was an unconventional enemy, it was that all they had to do was disrupt to win the information war. 300 civilians killed by a vehicle that explodes in a crowded market place? Message: “The Americans failed to protect.” A suicide bomber attacks a ribbon cutting ceremony for a new factory funded by the US government and the Iraqi provincial governor gets killed. Message: “This is what happens if you collaborate with the Americans.”

Warfare by spoiler meant AQI did not have to recruit. The presence of a large, occupying force did that for them. AQI did not even have to know each of their footmen. Individuals could self-recruit in reaction to a particularly rough night raid or with a checkpoint within sniper range of a rooftop.

“It was soon apparent that their changes were not the outcome of deliberate decision making by seniors in the hierarchy; they were organic reactions by forces on the ground. Their strategy was likely unintentional, but they had leveraged the new environment with exquisite success.”[5]

There’s nothing new under the sun — Except generational awareness

In response to an asymmetric threat that was not a worthy counterpart but nonetheless lethal adversary, the Task Force cultivated the organizational requirements of trust across internal tribal affinities, facilitated a sense of common purpose resulting in a shared consciousness (get on the same page) and empowered (de-centralized) execution. These characteristics are not in themselves, original or new concepts in organizational management. What Team of Teams offers that is different and groundbreaking is a compelling case based on the legitimacy and sheer improbability of their own experience. They invite you to a process leading to individual and organizational self-awareness.

What sets McChrystal’s leadership and team apart was their capacity for self-examination and the ability to compel this mindset across the Task Force. McChrystal credits this possibility to the fact the country was at war. This is true in part. Equally wartime compounds the pressure on tactics, resources and organizational dynamics in ways no training environment can duplicate. Therefore it remains considerable that such profound change was possible for an organization with arguably the highest degree of discipline, training, and accomplishment. If ever there was reason for arrogant tribalism to hold sway it was in Iraq in 2004. Instead, the Task Force leadership was open to and recognized a process which painfully required antithetical qualities on the frontlines of war: vulnerability, humility and the risk of internal divide and conquer.

Perhaps the most compelling reason to read this book is the experience from war and specifically that the war in question is Iraq. The transformation of the Task Force is not only a model for military and private sector application but any organization and including government.

Just as the Task Force did not get to fight the enemy it had trained for, we need the self-awareness to understand our role in the world as we find it, not the world as we would have it.

Persistent success in the modern world requires agility, the flexibility to anticipate disruption and the capacity to adapt and stay afloat. The problem is that the majority of people in power were not raised and socialized to function in an interdependent world and apace with the near-blinding rate of technological change. Like it or not, we are members of teams in our personal and professional lives. The instinct for tribalism, or retreating into what is familiar and known is a fundamental organizing principle which undergirds our society. Technological innovation and the unchecked exchange of information has catapulted our military, economy, and communities into the disruptive age and traditional authorities with clear lines of demarcation often no longer apply.

The reason to read Team of Teams is twofold: First, you cannot avoid the upheaval, whether as team leader or subordinate, company director or member of congress. Second, and not for the first time, the dynamic of war has fostered innovation that can illumine the shrouded pathway ahead for society writ large. The application of training, skill and resources applied to the high intensity stakes on the frontlines of combat has a way of concentrating the mind. Particularly when established knowledge says you should be winning, only you are aren’t.

Team of Teams proposes no single solution but a bespoke process leading to individual and organizational self-awareness. It is a powerful example and call for an honest examination starting with our assumptions and perceptions of ourselves. Just as the Task Force did not get to fight the enemy it had trained for, we need the self-awareness to understand our role in the world as we find it, not the world as we would have it. The stakes could not be higher. Failure to evolve from an outdated model of understanding to a dynamic, continually reviewed consciousness and we will fail to effectively engage our enemies and allies alike. So much of the past 14 years of war is a cautionary tale. The Task Force’s journey is proof that the greatest challenges hold the greatest opportunities.

Holly Hughson is a humanitarian aid worker with an extensive background in rapid assessment, program design, management and monitoring of operations in both humanitarian emergencies and post-conflict settings. Her experience includes work in Kosovo, Sudan, Iraq, Russian Federation and Afghanistan. Presently she is writing a personal history of war from the perspective of a Western female living and working in Muslim countries.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Christopher Fry, A Sleep of Prisoners. London: Oxford University Press, 1951.

[2] McChrystal, Stanley, Tantum Collins, David Silverman, and Chris Fussell,Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2015: 6.

[3] McChrystal, 20

[4] McChrystal, 21

[5] McChrystal, 224

2026: Operation Iranian Freedom

As I walk through my company’s assembly area, I face the insomnia and nervousness that millions of people have faced throughout history. I wonder if I have done enough to prepare my soldiers. I wonder how my father and my grandfather felt when they stood on this ground decades ago. I worry that I won’t bring credit upon the U.S. Army, my family, my fellow female commanders, and myself. No matter what the party line is, I know the actions taken by women in Operation Iranian Freedom will receive a high level of scrutiny. While I worry about the second and third order effects in this operation, especially the interactions between Iraq’s Sunni Arabs and the Iranian Shi’ia, I know I can only focus on what I can positively control. I can control my actions, I can influence those around me, and I can set a positive example for my soldiers.

A Reflection on a Room, Part I: A 1991 Diary Entry from Desert Storm

My entire life changed in that room. A large part of my life is still governed by that room, its intensity, the noise, the shouts, the laughter, the briefings, the questions, the fear of failing, and knowing that the lives of many were to be decided within that room. Adrenalin heightens awareness; and adrenaline flowed freely within the room; it wears you down and kills you, imperceptibly.

Out Jihad the Jihadi

In a lecture to field grade officers at the U.S. Army War College in 1981, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Maxwell Taylor described strategy as the sum of ends, ways and means; where ends are the objectives one strives for, ways are the course of action, and means are the instruments by which they are achieved.